Andean Journal of Education 9(1) (2026) 6002

Navigating the New Normal: Faculty Perception of Trust and Risks in Adopting Generative Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education

Navegando la nueva normalidad: percepción del profesorado sobre confianza y riesgos en la adopción de inteligencia artificial generativa en educación superior

Shakeel Iqbala

, Muhammad Naeem Khanb

, Muhammad Naeem Khanb

a Capital University of Science and Technology, Department of Management Sciences, Islamabad Expressway, Kahuta, Road Zone-V Sihala, 45750, Islamabad, Pakistan.

b Beaconhouse National University, School of Management Sciences, 13 KM Off Thokar Niazbeg, Raiwind Road, Tarogil, 53700, Lahore, Pakistan.

Received on September 02, 2025. Accepted on November 21, 2025. Published on January 21, 2026

https://doi.org/10.32719/26312816.6004

© 2026 Iqbal & Khan. CC BY-NC 4.0

Abstract

Generative AI (GenAI), exemplified by tools like ChatGPT, is increasingly popular in academia due to its potential to assist educators with tasks like lesson planning, personalized tutoring, and automated grading. However, it also presents challenges, including the risk of inaccurate or biased information, plagiarism, and negative effects on cognitive development. This study aims to explore the factors influencing GenAI adoption in higher education context. A study of 550 faculty members found that trust in GenAI content positively influences its adoption. The research, based on the UTAUT model, revealed that greater trust in GenAI is associated with a more positive outlook on its performance and ease of use, as well as a higher intention to adopt the technology. Furthermore, the study found that trust reduces the perceived risks of using GenAI, which further encourages adoption.

Keywords: generative AI, Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology, trust in GenAI, risks of GenAI, faculty perceptions

Resumen

La inteligencia artificial generativa (IA generativa), ejemplificada por herramientas como ChatGPT, es cada vez más popular en el ámbito académico debido a su potencial para asistir a los educadores en tareas como la planificación de clases, la tutoría personalizada y la calificación automatizada. Sin embargo, también presenta desafíos, como el riesgo de información inexacta o sesgada, el plagio y efectos negativos en el desarrollo cognitivo. Este estudio tiene como objetivo explorar los factores que influyen en la adopción de IA generativa en el contexto de educación superior. Un estudio con 550 profesores encontró que la confianza en el contenido de IA generativa influye positivamente en su adopción. La investigación, basada en el modelo UTAUT, reveló que mayor confianza en IA generativa se asocia con una perspectiva más positiva sobre su desempeño y facilidad de uso, así como con una mayor intención de adoptar la tecnología. Además, el estudio encontró que la confianza reduce los riesgos percibidos de usar IA generativa, lo que a su vez fomenta la adopción.

Palabras clave: IA generativa, Teoría Unificada de Aceptación y Uso de Tecnología, confianza en la IA generativa, riesgos de la IA generativa, percepciones del profesorado

Introduction

Generative artificial intelligence or “GenAI” refers to AI applications that employ diverse machine learning algorithms to generate original content. This content can take a multitude of forms, including, but not limited to, written text, images, videos, musical pieces, artwork, and even synthetic data (Mishra et al., 2023). While GenAI isn’t brand new, the arrival of OpenAI’s ChatGPT in late 2022 caused a huge stir, sparking conversations everywhere from news outlets to online discussions and academic circles (Ivanov et al., 2024). ChatGPT quickly captured the public’s attention and it is estimated to have garnered 100 million monthly active users in only two months. This unprecedented growth makes it the fastest-growing consumer application in history (Hu, 2023), showing just how transformative GenAI could be. Another GenAI app, DeepSeek —a Chinese AI startup— gained international recognition in January 2025. Its app topped download charts, even affecting U.S. tech stock prices. The company launched DeepSeek R1, an AI model claimed to rival OpenAI’s ChatGPT in capabilities but at a lower cost (Ng et al., 2025). DeepSeek’s user base grew to an estimated 5-6 million globally, with its app hitting number one on the US App Store on January 26, 2025 rising from its previous position at number 31 (Bæk, 2025).

GenAI is impacting many areas, especially education, where it has triggered a lot of debate. Because GenAI can potentially change how teachers teach and how students learn, educators have very different opinions about its widespread use. The fact that AI is becoming so advanced, and can even produce long, complex pieces of writing, has led to serious ethical questions about its role in educational institutions. ChatGPT is a prime example of this, compelling educational institutions to reconsider issues such as academic integrity and policy updates. (Hockly, 2023). Prestigious universities like Harvard and Oxford are responding by looking at their ethical guidelines and restating their commitment to academic integrity (Plata et al., 2023). In short, ChatGPT has made us reconsider our current rules and started a much broader conversation about how education can adapt to these powerful new AI tools, including how to address the ethical and practical issues they bring (Grassini, 2023).

GenAI applications such as ChatGPT hold significant promise for improving teaching and learning. Educators can leverage its capabilities for various tasks, such as streamlining lesson planning, offering personalized tutoring, automating grading, translating languages, fostering interactive learning, and implementing adaptive learning strategies (Baidoo-Anu & Ansah, 2023). GPT has the potential to personalize education by adapting learning content and assessments to the specific needs of each student. This personalized approach, facilitated by GenAI, is leading to a more intelligent and efficient educational landscape, creating exciting new opportunities for reform in both teaching and learning. Its diverse capabilities can alleviate teachers’ workloads by automating time-consuming administrative tasks without sacrificing quality (Watermeyer et al., 2024). The data-driven nature of AI can also provide

more objective and efficient feedback than human teachers (Celik et al., 2022). AI can also assist with student assessment and automated scoring, leveraging natural language processing for plagiarism detection and feedback (Banihashem et al., 2024). Furthermore, AI-powered Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITSs) can streamline student progress tracking, providing more effective monitoring of individual learning journeys (Celik et al., 2022; Chan & Tsi, 2024).

GenAI presents researchers with a multitude of possibilities. For example, ChatGPT’s comprehensive knowledge and advanced language processing make it a valuable tool for supporting technology research (OpenAI, 2023). It empowers researchers in numerous ways, from accessing information and analyzing data to identifying trends and generating creative content (Kalpokiene & Kalpokas, 2023). ChatGPT can facilitate comprehensive literature reviews, saving researchers time and effort by synthesizing relevant publications. It can also assist in identifying research gaps, formulating hypotheses, developing research questions and methodologies, and suggesting appropriate statistical analyses. Furthermore, ChatGPT helps researchers stay informed about current regulatory guidelines, including those related to safety, environmental issues and emerging technologies, thereby promoting adherence to best practices and industry standards (Rice et al., 2024).

While AI offers potential benefits, its limitations, especially regarding accuracy (reaching up to 90% error rates in some tasks, such as citation generation), cannot be ignored (Rice et al., 2024). Human oversight remains crucial. Scholars have long been exploring the potential impact of AI on teachers’ roles (e.g., Gentile et al., 2023; Nikitina & Ishchenko, 2024), and ChatGPT has brought these discussions to the forefront, posing unprecedented challenges to education (Peres et al., 2023). The broader discussion of AI-driven job displacement, with millions of jobs potentially at risk, has naturally led to speculation about the future of the teaching profession (Chan & Tsi, 2024).

Teacher Perceptions

The literature examining teachers’ perceptions of generative AI adoption in education reveals a sharply divided perspective. Some educators regard it as a significant opportunity, while others view it as a detrimental development. Amado et al. (2024) investigated how educators are using and experiencing generative AI in education. Their descriptive quantitative study of 80 active educators explored the integration of AI tools and technologies into teaching practices, including the challenges and perceived benefits. The findings revealed several challenges, including anxieties about job security, technological barriers, and ethical dilemmas. However, the study also identified opportunities for professional development, collaborative projects, and the potential of AI to address specific educational needs. According to the authors, successful integration of AI in academia depends on acknowledging and addressing both these challenges and opportunities.

According to a study by Chan and Tsi (2024), most university students and teachers in Hong Kong believe that human teachers possess irreplaceable qualities such as critical thinking and emotional intelligence. The survey, which included 399 students and 184 teachers, found that most participants were not worried about generative AI (GenAI) replacing teachers. Instead, they recognized the importance of human teachers for social-emotional development through direct interaction. The authors suggest that rather than fearing replacement, teachers should explore integrating GenAI to enhance learning. Another study involving 358 Middle Eastern faculty members found that their use of Generative AI for student assessment was influenced by perceived benefits, ease of use, and social influence Khlaif et al. (2024). While instructors see benefits such as increased engagement, they worry about academic integrity and negative effects on students’ writing and critical thinking.

Alwaqdani (2024) surveyed 1,101 Saudi teachers to explore their views on AI in education (AIED). The study investigated AIED’s potential to enhance teaching and the challenges teachers face when using it. While many teachers recognized AIED’s potential for saving time, personalizing learning, and designing enriching activities, they also expressed concerns. The concerns raised included the effort required for training, the potential for job displacement, the possibility that creativity and critical thinking skills could diminish and whether AI could be reliably trusted. Overall, the teachers expressed cautious optimism about AIED, weighing its benefits against concerns related to educational quality, the human element, and potential risks.

Research Gap

Existing research on Generative AI (GenAI) adoption is lacking in two key areas. First, it does not adequately address the perspectives of teachers, focusing more on students. This leaves a gap in understanding the unique challenges and opportunities that teachers face when using GenAI. Second, the literature has not thoroughly explored the crucial roles of trust and perceived risks in GenAI adoption. Teachers’ willingness to use the technology is likely tied to their trust in its accuracy and their concerns about issues such as plagiarism and data privacy. This study aims to fill these gaps by focusing specifically on teachers’ views on trust and perceived risks in order to help inform better strategies for integrating GenAI into education.

Literature Review & Hypotheses

Trust in GenAI

In today’s digital landscape, user trust is paramount, especially when individuals are asked to share information with AI-driven tools and applications. This concern about trust is particularly relevant for AI tools such as chatbots, where users often interact with them on a personal level. Cultivating trust in these AI systems, including ChatGPT, is crucial for promoting their adoption (Menon & Shilpa, 2023). If users do not trust the AI, they are far less likely to use it. Several factors contribute to this perceived trust, including the system’s reliability (consistently performing as expected), transparency (a clear understanding of how the system works), and accountability (mechanisms for addressing errors or issues).

Existing research has shown that perceived trust (PT) strongly influences the intention to adopt AI tools across various sectors. Studies have shown that in banking, education, and tourism perceived trust is a significant factor influencing whether users are willing to use AI-powered services (Choi et al., 2023; Rahman et al., 2023; Ayoub et al., 2024; Bhaskar et al., 2024). These studies provide empirical evidence that when users trust an AI system, they are more inclined to adopt it. Building on this body of research, we hypothesize that:

H1: Trust in GenAI positively influences adoption of GenAI.

According to Baek and Kim (2023), users are more receptive to and engage more with AI technologies they trust. This trust is not static; as users gain more experience with ChatGPT and its capabilities, their trust can either grow, leading to increased engagement, or diminish, hindering adoption. This evolving trust directly impacts users’ perceptions of effort expectancy (how much effort is required to use the system) and performance expectancy (the belief that using the system will lead to desired outcomes). If users trust ChatGPT, they are more likely to believe it will be easy to use and effective in achieving their goals. Conversely, a lack of trust can create a perception of difficulty and ineffectiveness.

Furthermore, users’ awareness of ChatGPT significantly influences their perceptions of its ease of use. As familiarity with the system and its functionalities grows, users’ expectations and attitudes regarding its usability also evolve. Initial experiences, both positive and negative, shape these perceptions. However, trust plays a moderating role in this relationship. As Ali et al. (2023) argue, trust in ChatGPT, built upon factors such as reliability, transparency, and ethical considerations, influences how users interpret their awareness of the technology. High levels of trust can amplify the positive impact of awareness on perceived ease of use, whereas low trust can diminish or even negate it (Shahzad et al., 2024). In essence, trust acts as a filter, shaping users’ cognitive and emotional responses to ChatGPT and ultimately influencing their overall experience with the AI.

This evolving trust directly impacts users’ perceptions of effort expectancy (how much effort is required to use the system) and performance expectancy (the belief that using the system will lead to desired outcomes). If users trust ChatGPT, they are more likely to believe it will be easy to use and effective in achieving their goals. Conversely, a lack of trust can create perceptions of difficulty and ineffectiveness (Bhaskar et al., 2024). User awareness of ChatGPT has a significant impact on how easy they find it to use. As familiarity with the system and its functionalities grows, users’ expectations and attitudes also evolve. The above discussion leads us to the following hypotheses:

H2: Trust in GenAI positively influences Performance expectancy of GenAI.

H3: Trust in GenAI positively influences Effort expectancy of GenAI.

Perceived Risks and GenAI Adoption

Several potential risks associated with GenAI in education have raised concerns among educators and researchers. These risks include the perpetuation of biases present in the data on which GenAI is trained, ethical dilemmas surrounding plagiarism and the ownership of AI-generated work, and fundamental questions about academic integrity (Dwivedi et al., 2023; Ivanov & Soliman, 2023). These concerns are not merely abstract; they can significantly affect teachers’ and students’ attitudes toward GenAI.

This connection between trust, perceived risk, and intention has been explored in previous research across different domains. For example, employing the UTAUT model, Schaupp et al. (2010) found that trust in an e-filing system was negatively related to perceived risk, which, in turn, negatively influenced the intention to use the system. This suggests that higher trust leads to lower perceived risk, thereby increasing the likelihood of adoption. Similarly, McLeod et al. (2008) proposed that perceived risk acts as a mediator between trust and behavioral intention, meaning that trust influences intention indirectly through its effect on perceived risk. TAM-based research also indicates that higher trust leads to lower perceived risk, which in turn leads to lower behavioral intention (Pavlou, 2003; Thiesse, 2007). These findings consistently demonstrate that trust is crucial for mitigating perceived risk, which ultimately drives adoption. Thus we hypothesize:

H4: Trust in GenAI negatively influences Perceived risks of GenAI.

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) suggests that attitudes are shaped by the perceived outcomes of a behavior. The risks associated with GenAI, such as those mentioned above, can easily lead to negative attitudes toward its use in education (Ivanov et al., 2024). If educators and students perceive GenAI as a tool that could compromise academic honesty or reinforce existing biases, they are likely to develop negative feelings about its adoption. Furthermore, societal and educational norms that prioritize traditional methods and value human-created work can amplify these negative attitudes. If the prevailing expectation is risk-averse, it is logical to assume that perceived risks will also negatively influence subjective norms – the perceived social pressure to adopt or not adopt GenAI (Wu et al., 2022). In other words, if teachers believe their colleagues and institutions disapprove of GenAI, they will be less likely to use it themselves.

Finally, TPB posits that perceived behavioral control, the belief in one’s ability to successfully perform a behavior, is a key driver of intention. Perceived risks associated with GenAI can undermine this sense of control (Ivanov et al., 2024). If teachers feel they lack the training, support, or understanding to effectively and ethically integrate GenAI, or if they fear the potential negative consequences, they are less likely to implement it in their classrooms. They may feel overwhelmed by the potential challenges and thus less confident in their ability to use GenAI successfully. Hence, we hypothesize:

H5: Perceived Risks of GenAI negatively influence adoption of GenAI.

Performance Expectancy and GenAI adoption

Performance expectancy, as defined by Wong et al. (2013), reflects an individual’s belief that using a particular technology will improve their job performance and, consequently, their career prospects. Numerous studies have demonstrated a strong, positive, and direct link between performance expectancy and both the intention to use technology and its actual adoption (Wong et al., 2013; Teo & Milutinovic, 2015). Some researchers (e.g., Mohammed et al., 2018) even identified it as the strongest predictor of technology adoption. This is consistent with findings that teachers are more likely to embrace and utilize technology if they believe it will enhance their performance (Proctor & Marks, 2013). The widespread use of performance expectancy in understanding teachers’ intentions to adopt ICTs is also highlighted by Cviko et al. (2012).

Venkatesh et al. (2003) pointed out that performance expectancy (PE) is composed of several related factors, including perceived usefulness, relative advantage, job fit, extrinsic motivation, and outcome expectation. From a consumer perspective, it is defined as the extent to which using a technology provides benefits in performing specific activities (Venkatesh et al., 2012). Generally, performance expectancy is the belief that technology can make tasks easier and faster, improve job performance, and boost productivity (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Research consistently shows that performance expectancy is a significant predictor of positive attitudes towards technology (Patil et al., 2020). In essence, perceived usefulness is key to shaping attitudes toward technology (Dwivedi et al., 2019). Therefore we hypothesize:

H6: Performance expectancy has a positive impact on GenAI adoption.

Effort Expectancy and GenAI Adoption

Many people perceive generative AI as both user-friendly and effortless, as pointed out by Naujoks et al. (2024) as well. This positive perception is driven by the increasing focus on intuitive design, the automation of routine tasks, and the seamless integration of technology into daily life. As a result, technology is often regarded as an enabler that simplifies complex processes and empowers users to achieve more with less effort. The literature supports this view, demonstrating a significant and positive direct impact of “effort expectancy” on the intention to use technology (Khan et al., 2019; Camilleri, 2024). This suggests that instructors recognize the potential of technology to reduce the effort required for their tasks, which, in turn, increases their intention to use ICT. Some research also indicates an indirect relationship between effort expectancy and ICT usage intention (Teo, 2009). When teachers perceive ICT as easy to use, their expectations and belief in its potential to enhance their performance also increase (Zhou et al., 2010).

Effort expectancy (EE), as defined by Venkatesh et al. (2003), encompasses several related constructs, including perceived ease of use, perceived complexity, and perceived ease of learning. Essentially, EE reflects the individual’s belief about the ease of using a particular technology. It highlights the relationship between effort invested, resulting performance outcomes, and any resulting rewards (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Numerous studies have found a positive and significant relationship between effort expectancy and attitude toward technology (Camilleri, 2024). For successful adoption, systems should be easy to learn, use, and understand. Interactions between users and vendors should be comfortable, flexible, and require minimal effort. The learning process for new technologies should be comprehensible, efficient, and straightforward. In the Meta-UTAUT analysis, effort expectancy emerged as a significant predictor of and strongly related to attitude (Dwivedi et al., 2019). Based on these findings, it is hypothesized that Pakistani teachers, in pursuit of effective effort management, will exhibit positive intentions toward technology adoption.

H7: Effort expectancy has a positive impact on GenAI adoption.

Social Influence and GenAI adoption

Social influence, as described by Yu (2012), refers to the perceived social pressure to engage in or abstain from specific behaviors. Arif et al. (2016) define it as an individual’s perception of how others will view their actions. Im et al. (2011) highlight the impact of social circles, including friends, influential figures, and family, on technology adoption. While some research suggests a weak or indirect influence of social factors on ICT adoption intention (Wong et al., 2013; Teo & Zhou, 2014), other studies have found a significant and direct impact (Teo & Milutinovic, 2015). Wong et al. (2013) specifically notes the influence of friends, colleagues, and peers on intention.

According to Venkatesh et al. (2003), social influence (SI) operates through the sharing of information, recommendations, and assistance, impacting an individual’s choices based on the influence of their social network. When individuals value the opinions of others’ in their decision-making process, social influence becomes a powerful motivator for adopting new systems (Brata & Amalia, 2018). Venkatesh et al. (2012) demonstrated the significant impact of social influence on consumer technology acceptance. Numerous studies on technology acceptance have explored the relationship between social influence and behavioral intention, consistently finding positive and significant links (Friedrich et al., 2021). Given the collectivist nature of Pakistani society, teachers there are likely to be influenced by their social networks regarding ICT adoption. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H8: Social influence will have a direct and significant impact on teachers’ adoption of generative AI.

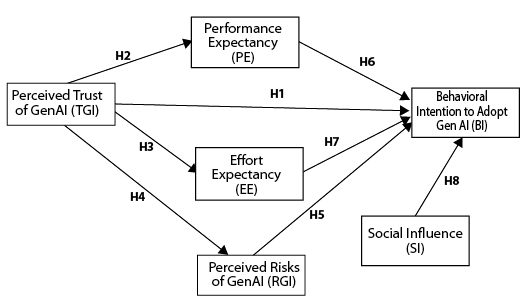

Proposed Research Model

Figure 1 given below shows the conceptual model for this research:

Figure 1: Proposed Research Model

Methodology

Population and Sampling

The target population for this study comprises the faculty members at higher education institutions in Pakistan. The study aimed to collect a sufficient number of responses to ensure the statistical power of the subsequent analyses, particularly given the use of structural equation modeling (SEM). As noted in the literature, a sample size of 200 or more respondents is generally recommended for studies employing SEM to achieve adequate statistical power and stable parameter estimates (e.g., Kline, 2023). Data were collected from respondents using convenience sampling. While this non-probability technique lacks the rigor of random sampling, it is often selected by researchers for its practicality under time and budgetary constraints.

Instrument and Measures

To ensure the questionnaire accurately captured teachers’ views on generative AI in education, the study used a thorough design process. Three AI and education experts reviewed the questions to ensure they were easily understandable for teachers. The questionnaire was created using items from previously validated studies, with new questions added to specifically address teachers’ trust in, and perceived risks associated with GenAI. A 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree), was used to measure the intensity of the teachers’ responses.

Table 1. Measurement Constructs and Sources.

|

Construct |

Source |

|

Performance Expectancy (PE) |

|

|

Effort Expectancy (EE) |

|

|

Social Influence (SI) |

Venkatesh et al. (2003) |

|

Facilitating Conditions (FC) |

Venkatesh et al. (2003) |

|

Perceived Risk (PR) |

|

|

Trust (TR) |

Al-Abdullatif (2024); Authors |

|

Behavioral Intention (BI) |

Venkatesh et al. (2003) |

|

|

Data Analysis and Results

Data collection for this study exploring university teachers’ perceptions of GenAI involved distributing questionnaires to faculty members across all the universities in Pakistan. To maximize participation, a mixed-mode approach was employed, using both traditional paper-based questionnaires and online survey platforms. A total of 731 responses were initially collected. However, 181 responses were removed from the dataset to ensure its quality and validity. The excluded responses were either incomplete, carelessly completed, or identified as statistical outliers. After this thorough cleaning process, the final dataset consisted of 550 complete and valid responses. These responses formed the basis for the subsequent data analysis, which was conducted using two specialized statistical software packages: SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) and SmartPLS (Partial Least Squares).

Validity and Reliability

To assess the potential presence of common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The results of the exploratory factor analysis indicated that the first factor accounted for 36.009% of the total variance, which is below the commonly accepted threshold of 50% (Podsakoff et al., 2003). This suggests that common method bias was not a significant concern in this study. Furthermore, the cumulative variance explained by the first six factors was 89.806%, confirming a multifactor structure, which further reduces the likelihood of bias influencing the results.

Factor Analysis

Table 2 presents the results for indicator loadings, Cronbach’s Alpha, Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for all constructs. The indicator loadings for all items exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.7 (Hair et al., 2019), confirming strong item reliability. The Cronbach’s Alpha values ranged from 0.935 to 0.98, well above the acceptable threshold of 0.7 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994), ensuring strong internal consistency. The CR values for all constructs exceeded 0.9, further demonstrating the robustness of the measures. Additionally, the AVE values for all constructs were well above the recommended 0.5 threshold (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), ensuring sufficient convergent validity.

Table 2. Construct loading, convergent validity, and reliability analysis.

|

Construct |

Indicator |

Indicator Loading |

Alpha |

CR |

AVE |

|

Trust |

TrustQ1 |

0.921 |

0.954 |

0.955 |

0.84 |

|

TrustQ2 |

0.936 |

||||

|

TrustQ3 |

0.926 |

||||

|

TrustQ4 |

0.883 |

||||

|

Performance Expectancy |

PEQ1 |

0.931 |

0.962 |

0.962 |

0.864 |

|

PEQ2 |

0.941 |

||||

|

PEQ3 |

0.932 |

||||

|

PEQ4 |

0.915 |

||||

|

Effort Expectancy |

EEQ1 |

0.908 |

0.941 |

0.943 |

0.842 |

|

EEQ2 |

0.905 |

||||

|

EEQ3 |

0.939 |

||||

|

Perceived Risk |

PRQ1 |

0.941 |

0.98 |

0.98 |

0.872 |

|

PRQ2 |

0.915 |

||||

|

PRQ3 |

0.945 |

||||

|

PRQ4 |

0.949 |

||||

|

PRQ5 |

0.909 |

||||

|

PRQ6 |

0.941 |

||||

|

PRQ7 |

0.938 |

||||

|

Social Influence |

SIQ1 |

0.887 |

0.935 |

0.936 |

0.829 |

|

SIQ2 |

0.926 |

||||

|

SIQ3 |

0.917 |

||||

|

Behavioral Intention |

BIQ1 |

0.974 |

0.977 |

0.978 |

0.914 |

|

BIQ2 |

0.964 |

||||

|

BIQ3 |

0.922 |

||||

|

BIQ4 |

0.962 |

||||

|

|

|

Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity was assessed using Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) criterion and the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT). Table 3 presents the correlation matrix, where the square root of the AVE values (bolded on the diagonal) is greater than the correlation coefficients between constructs, confirming adequate discriminant validity. The HTMT values (in parentheses) for all constructs remain well below the 0.90 threshold (Henseler et al., 2015), further confirming that each construct is empirically distinct. Notably, the highest HTMT value is 0.508 between Trust and Behavioral Intention, which is well within the acceptable range. This suggests that there are no issues of multicollinearity or construct redundancy, ensuring the validity of the measurement model.

Table 3. Correlation matrix and Discriminant validity analysis.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

Trust |

0.917 |

|||||

|

PE |

0.489 |

0.93 |

||||

|

(0.491) |

||||||

|

EE |

0.384 |

0.187 |

0.918 |

|||

|

(0.386) |

(0.098) |

|||||

|

PR |

-0.477 |

-0.183 |

-0.233 |

0.934 |

||

|

(0.481) |

(0.206) |

(0.225) |

||||

|

SI |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.91 |

|

|

(0.018) |

(0.047) |

(0.034) |

(0.021) |

|||

|

BI |

0.506 |

0.413 |

0.342 |

-0.366 |

0.242 |

0.956 |

|

(0.508) |

(0.385) |

(0.339) |

(0.373) |

(0.241) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note: Values in bold are square root of AVE, and in parentheses are HTMT.

Model Fitness

The model fit indices were assessed using Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), d_ULS, d_G, Chi-square, and Normed Fit Index (NFI) as shown in the table 4 below. The SRMR values were 0.015 (saturated model) and 0.026 (estimated model), both of which fall below the recommended threshold of 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999), indicating a good model fit. SRMR values close to zero suggest that the difference between the observed and predicted covariance matrices is minimal, thereby confirming the appropriateness of the model.

The d_ULS (0.095 for the saturated model and 0.301 for the estimated model) and d_G (0.098 for the saturated model and 0.103 for the estimated model) provide additional evidence of good model fit. Lower values of these discrepancy indices indicate a smaller deviation between the empirical and model-implied covariance matrices (Henseler et al., 2014). The Chi-square values of 279.049 (saturated model) and 295.269 (estimated model) suggest a reasonable fit, considering that Chi-square is sensitive to large sample sizes. Although a lower Chi-square value is desirable, it is recommended that this statistic be interpreted in conjunction with other fit indices (Hair et al., 2019). The NFI values of 0.985 (saturated model) and 0.984 (estimated model) exceed the recommended threshold of 0.90 (Bentler & Bonett, 1980), indicating a well-fitting model. The NFI compares the Chi-square value of the hypothesized model with a null model, where higher values indicate better model fit.

|

Saturated model |

Estimated model |

|

|

SRMR |

0.015 |

0.026 |

|

d_ULS |

0.095 |

0.301 |

|

d_G |

0.098 |

0.103 |

|

Chi-square |

279.049 |

295.269 |

|

NFI |

0.985 |

0.984 |

|

|

|

|

Hypothesis Testing and Discussion

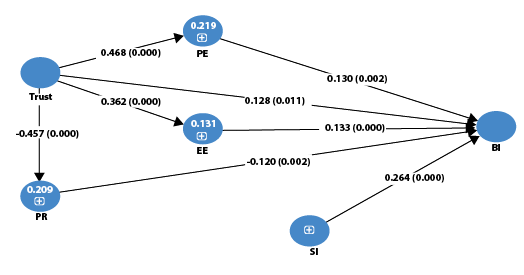

The hypothesis-testing results are presented in table 5 below. The results reveal that Social Influence (SI) had the strongest positive effect on Behavioral Intention (BI) (β = 0.264, p < 0.001), followed by Effort Expectancy (EE → BI; β = 0.133, p < 0.001) and Performance Expectancy (PE → BI; β = 0.130, p = 0.002). Trust also had a significant positive impact on BI (β = 0.128, p = 0.011), whereas Perceived Risk (PR) negatively influenced BI (β = -0.120, p = 0.002). Trust exhibited a strong positive effect on Performance Expectancy (β = 0.468, p < 0.001) and a negative effect on Perceived Risk (β = -0.457, p < 0.001).

The findings indicate that Social Influence plays a critical role in shaping individuals’ behavioral intentions. This suggests that peer recommendations and societal trends significantly impact technology adoption. The positive effects of effort expectancy and performance expectancy imply that users are more inclined to adopt technology when it is easy to use and provides clear benefits. The significant role of trust further underscores the importance of building credibility and confidence in digital platforms to enhance user adoption rates.

On the other hand, perceived risk negatively impacts behavioral intention, indicating that concerns about security, privacy, and potential losses discourage users from adopting technology. This aligns with prior research emphasizing the need for risk mitigation strategies to enhance user trust.

Additionally, mediation effects were examined. Trust indirectly influenced BI through its effects on PR (β = 0.055, p = 0.002), PE (β = 0.061, p = 0.003), and EE (β = 0.048, p = 0.000), confirming the mediating role of these constructs. These results suggest that fostering trust can mitigate perceived risks and enhance performance expectations, ultimately promoting greater technology adoption. However, demographic variables (Age, Education, Experience, and Gender) did not exhibit significant effects on BI (p > 0.05), suggesting that behavioral intention is primarily driven by psychological and contextual factors rather than demographic attributes. The insignificance of demographic factors highlights that technology adoption is influenced more by perceptions of usefulness and ease of use rather than by personal background characteristics.

Table 5. Hypotheses Test Results.

|

Hypotheses |

Direct path |

B |

SE |

T value |

P values |

Indirect paths |

97% confidence Interval |

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

|||||||

|

EE -> BI |

Direct |

0.133 |

0.037 |

3.629 |

0.000 |

0.060 |

0.205 |

|

|

PE -> BI |

Direct |

0.130 |

0.046 |

2.858 |

0.002 |

0.038 |

0.220 |

|

|

PR -> BI |

Direct |

-0.120 |

0.041 |

2.907 |

0.002 |

-0.200 |

-0.038 |

|

|

SI -> BI |

Direct |

0.264 |

0.038 |

7.012 |

0.000 |

0.190 |

0.338 |

|

|

Trust -> BI |

Direct Indirect Total |

0.128 0.164 0.292 |

0.056 0.039 0.047 |

2.292 4.488 6.425 |

0.011 0.000 0.000 |

Trust -> PR -> BI Trust -> PE -> BI Trust -> EE -> BI |

0.018 0.096 0.200 |

0.237 0.232 0.380 |

|

Trust -> EE |

Direct |

0.362 |

0.036 |

10.135 |

0.000 |

0.292 |

0.431 |

|

|

Trust -> PE |

Direct |

0.468 |

0.032 |

14.708 |

0.000 |

0.403 |

0.530 |

|

|

Trust -> PR |

Direct |

-0.457 |

0.033 |

13.748 |

0.000 |

-0.522 |

-0.393 |

|

|

Trust -> PR -> BI |

Indirect |

0.055 |

0.019 |

2.828 |

0.002 |

0.018 |

0.094 |

|

|

Trust -> PE -> BI |

Indirect |

0.061 |

0.022 |

2.797 |

0.003 |

0.018 |

0.105 |

|

|

Trust -> EE -> BI |

Indirect |

0.048 |

0.014 |

3.379 |

0.000 |

0.021 |

0.077 |

|

|

Age -> BI |

Control |

0.013 |

0.040 |

0.321 |

0.748 |

-0.065 |

0.091 |

|

|

Education -> BI |

Control |

0.013 |

0.038 |

0.359 |

0.720 |

-0.062 |

0.085 |

|

|

Experience -> BI |

Control |

-0.033 |

0.039 |

0.836 |

0.403 |

-0.110 |

0.045 |

|

|

Gender -> BI |

Control |

-0.014 |

0.038 |

0.363 |

0.716 |

-0.090 |

0.060 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 2 below shows the standardized path coefficients:

Figure 2: Results of Standardized path coefficients (*p- value <0.05, **p-value < 0.001)

Discussion of Results and Implications

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into how teachers perceive generative AI (GenAI) and the factors influencing its adoption in educational settings. Specifically, the results highlight the critical roles of trust, risk perception, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence in shaping teachers’ willingness to adopt GenAI.

One of the most significant findings of this study is that trust in GenAI positively influences its adoption among teachers. When educators perceive GenAI as reliable and beneficial, they are more likely to integrate it into their teaching practices. This aligns with existing research suggesting that trust plays a fundamental role in the adoption of emerging technologies, particularly in high-stakes environments such as education. Trust not only fosters a positive attitude toward AI but also encourages teachers to explore its potential in enhancing classroom experiences.

Furthermore, trust in GenAI was found to negatively influence teachers’ risk perceptions. This suggests that when educators have confidence in the capabilities and ethical considerations of GenAI, they are less likely to be concerned about its potential drawbacks, such as bias, misinformation, or lack of pedagogical effectiveness. This inverse relationship highlights the need for AI developers and policymakers to prioritize transparency, ethical AI design, and clear communication about AI’s limitations and benefits to build trust among educators.

The study also found that trust in GenAI strongly influences both performance expectancy and effort expectancy. Performance expectancy refers to the extent to which teachers believe that using GenAI will enhance their teaching effectiveness, while effort expectancy relates to how easy they perceive it to be to use GenAI in their workflows.

When teachers trust GenAI, they are more likely to expect positive outcomes from its use, such as enhanced lesson planning, personalized student feedback, and increased efficiency. Similarly, higher trust levels reduce perceived complexity, making teachers feel more confident in their ability to integrate GenAI into their practices. Both of these factors—performance expectancy and effort expectancy—positively influence GenAI adoption, emphasizing the importance of user-friendly AI tools that provide clear benefits in educational contexts.

Perceived risks negatively impact the adoption of Generative AI (GenAI) among teachers. Concerns over data privacy, ethical issues, and over-reliance on AI-generated content make teachers less likely to use the technology. To encourage adoption, educational institutions should create clear guidelines for responsible AI use. Developers must also prioritize ethical AI frameworks, data security, and user control. Additionally, training programs can help teachers understand and mitigate these risks.

Social influence significantly encourages teachers to adopt Generative AI (GenAI). When colleagues and administrators support and promote the use of GenAI, teachers are more likely to use it. This highlights the importance of creating a supportive institutional environment. Educational institutions can boost adoption by encouraging teachers to share best practices, collaborate on AI-driven lessons, and learn from successful early adopters.

There appears to be a consensus among teachers and students that generative AI cannot replace the human qualities of teachers that are essential for facilitating students’ generic competency development and personal growth. However, as generative AI is set to become a prominent feature in many areas of everyday life, higher education institutions need to rethink how curricula can be designed to capitalize on the human qualities of teachers and the potential of generative AI to transform learning. Ultimately, creating a synergy between humans and technology is key to success in an AI-dominated world. (Chan & Tsi, 2024).

Theoretical Implications

This study offers important theoretical implications for understanding the roles of trust and risk in technology adoption, particularly within the context of GenAI in education. The findings highlight the crucial role of trust in fostering positive perceptions of GenAI and mitigating perceived risks. This underscores the need for future research to further explore the mechanisms through which trust is built and how perceived risks can be effectively addressed to facilitate the successful integration of GenAI into educational settings. By demonstrating the significant impact of these variables, this study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the psychological and social factors that influence technology adoption beyond the traditional UTAUT constructs.

Practical Implications

In order to strengthen faculty trust and encourage the adoption of Generative AI (GenAI), universities should take a multi-pronged approach. First, prioritize transparent communication about the tools, highlighting their capabilities, limitations, and how data are used. Showcasing success stories from faculty can also build trust through positive peer influence. Second, universities should leverage social influence by creating communities where teachers can share experiences and best practices. Identifying and supporting GenAI champions can also help mentor colleagues. Finally, universities must address perceived risks head-on. They should offer targeted training to address concerns like plagiarism and data accuracy, while providing clear ethical guidelines and emphasizing the need for critical evaluation of GenAI-generated content.

To help teachers adopt Generative AI, they should focus on its practical applications and ease of use. Teachers can start by exploring how GenAI can benefit their work, such as by generating lesson plans or personalizing feedback. By starting with small-scale experiments and sharing best practices, they can build confidence and skills. Meanwhile, GenAI developers must prioritize building user trust. They should enhance the transparency and accuracy of their models, and provide clear documentation on their tools’ capabilities and limitations. Additionally, developers should create user-friendly interfaces with accessible tutorials to facilitate adoption.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was limited, which affects the generalizability of the findings. Second, the use of convenience sampling may introduce bias, as the participants might not fully represent all university teachers. Third, the use of self-reported data could lead to inaccuracies from social desirability or recall issues. Fourth, the study’s broad approach across different subjects might hide important differences between disciplines. Finally, the research only provides a snapshot in time, so it can’t capture changes in perception over time.

Statement on use of LLM

A Large Language Model, specifically Gemini 2.5 Pro, was used solely as a writing assistant for editing, grammar checks, and enhancing the clarity and conciseness of the final text. The author retains full responsibility for the content, scientific integrity, and conclusions presented in this paper.

References

Al-Abdullatif, A. (2024). Modeling Teachers’ Acceptance of Generative Artificial Intelligence Use in Higher Education: The Role of AI Literacy, Intelligent TPACK, and Perceived Trust. Education Sciences, 14(11), 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14111209

Ali, F., Yasar, B., Ali, L., & Dogan, S. (2023). Antecedents and Consequences of Travelers’ Trust towards Personalized Travel Recommendations Offered by ChatGPT. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2023.103588

Alwaqdani, M. (2024). Investigating Teachers’ Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence Tools in Education: Potential and Difficulties. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 2737-2755. https://tinyurl.com/4khths77

Amado, H., Morales, M., Hernandez, R., & Rosales, M. (2024). Exploring Educators’ Perceptions: Artificial Intelligence Integration in Higher Education. Paper presented in the 2024 IEEE World Engineering Education Conference (EDUNINE), Guatemala City, March 10-13. https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUNINE60625.2024.10500578

Arif, I., Aslam, W., & Ali, M. (2016). Students’ Dependence on Smartphones and Its Effect on Purchasing Behavior. South Asian Journal of Global Business Research, 5(2), 285-302. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJGBR-05-2014-0031

Ayoub, D., Metawie, M., & Fakhry, M. (2024). AI-ChatGPT Usage Among Users: Factors Affecting Intentions to Use and the Moderating Effect of Privacy Concerns. MSA-Management Sciences Journal, 3(2), 120-152. https://doi.org/10.21608/msamsj.2024.265212.1054

Bæk, D. (2025). Deepseek Users & Downloads. SEO.Ai. January 28. https://tinyurl.com/mrbu5fwt

Baek, T. H., & Kim, M. (2023). Is ChatGPT Scary Good? How User Motivations Affect Creepiness and Trust in Generative Artificial Intelligence. Telematics and Informatics, 83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2023.102030

Baidoo-Anu, D., & Owusu Ansah, L. (2023). Education in the Era of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI): Understanding the Potential Benefits of ChatGPT in Promoting Teaching and Learning. Journal of AI, 7(1), 52-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4337484

Banihashem, S., Kerman, N., Noroozi, O., Moon, J., & Drachsler, H. (2024). Feedback Sources in Essay Writing: Peer-Generated or AI-Generated Feedback? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1). https://tinyurl.com/3d6jjyup

Bentler, P., & Bonett, D. (1980). Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588-606. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Bhaskar, P., Misra, P., & Chopra, G. (2024). Shall I Use ChatGPT? A Study on Perceived Trust and Perceived Risk towards ChatGPT Usage by Teachers at Higher Education Institutions. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 41(4), 428-447. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-11-2023-0220

Brata, A., & Amalia, F. (2018). Impact Analysis of Social Influence Factor on Using Free Blogs as Learning Media for Driving Teaching Motivational Factor. Paper presented in the ICFET ’18: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Frontiers of Educational Technologies, Moscow, June 25-27. https://doi.org/10.11 45/3233347.3233360

Camilleri, M. (2024). Factors Affecting Performance Expectancy and Intentions to Use ChatGPT: Using SmartPLS to Advance an Information Technology Acceptance Framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123247

Celik, I., Dindar, M., Muukkonen, H., & Järvelä, S. (2022). The Promises and Challenges of Artificial Intelligence for Teachers: A Systematic Review of Research. TechTrends, 66(4), 616-630. https://tinyurl.com/5dwtp5ea

Chan, C., & Tsi, L. (2024). Will Generative AI Replace Teachers in Higher Education? A Study of Teacher and Student Perceptions. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2024.101395

Choi, S., Jang, Y., & Kim, H. (2023). Influence of Pedagogical Beliefs and Perceived Trust on Teachers’ Acceptance of Educational Artificial Intelligence Tools. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 39(4), 910-922. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2049145

Cviko, A., McKenney, S., & Voogt, J. (2012). Teachers Enacting a Technology-Rich Curriculum for Emergent Literacy. Educational Technology Research and Development, 60, 31-54. https://tinyurl.com/ycyt8tv2

Dwivedi, Y., Rana, N., Jeyaraj, A., Clement, M., & Williams, M. (2019). Re-Examining the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT): Towards a Revised Theoretical Model. Information Systems Frontiers, 21, 719-734. https://tinyurl.com/yhcxdfzj

Dwivedi, Y., Kshetri, N., Hughes, L., Slade, E., Jeyaraj, A., Kar, A., Baabdullah, A., Koohang, A., Raghavan, V., Ahuja, M., Albanna, H., Albashrawi, M., Al-Busaidi. A., Balakrishnan, J., Barlette, Y., Basu, S., Bose, I., Brooks, L., Buhalis, D., Carter, L., Chowdury, S., Crick, T., Cunningham, S., Davies, G., Davison, R., Dé, R., Dennehy, D., Duan, Y., Dubey, R., Dwivedi, R., Edwards, J., Flavián, C., Gauld, R., Grover, V., Hu, M., Janssen, M., Jones, P., Junglas, I., Khorana, S., Kraus, S., Larsen, K., Latreille, P., Laumer, S., Malik, F., Mardani, A., Mariani, M., Mithas, S., Magaji, E., Nord, J., O’Connor, S., Okumus, F., Pagani, M., Pandey, N., Papagiannidis, S., Pappas, I., Pathak, N., Pries-Heje, J., Raman, R., Rana, N., Rehm, S., Ribeiro-Navarrete, S., Richter, A., Rowe, F., Sarker, S., Stahl, B., Tiwari, M., Van der Aalst, W., Venkatesh, V., Viglia, G., Wade, M., Walton, P., Wirtz, J., & Wright, R. (2023). Opinion Paper: “So What if ChatGPT Wrote It?”: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Opportunities, Challenges and Implications of Generative Conversational AI for Research, Practice and Policy. International Journal of Information Management, 71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102642

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Friedrich, T., Schlauderer, S., & Overhage, S. (2021). Some Things Are Just Better Rich: How Social Commerce Feature Richness Affects Consumers’ Buying Intention Via Social Factors. Electronic Markets, 31, 159-180. https://tinyurl.com/4f748a3e

Gentile, M., Città, G., Perna, S., & Allegra, M. (2023, March). Do We Still Need Teachers? Navigating the Paradigm Shift of the Teacher’s Role in the AI Era. Frontiers in Education, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1161777

Grassini, S. (2023). Shaping the Future of Education: Exploring the Potential and Consequences of AI and ChatGPT in Educational Settings. Education Sciences, 13(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070692

Hair, J., Risher, J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. (2019). When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2-24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Henseler, J., Dijkstra, T., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C., Diamantopoulos, A., Straub, D., Ketchen, D., Hair, J., Hult, G., & Calantone, R. (2014). Common Beliefs and Reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organizational research methods, 17(2), 182-209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114526928

Henseler, J., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115-135. https://tinyurl.com/2s45j7t7

Hockly, N. (2023). Artificial Intelligence in English Language Teaching: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. RELC Journal, 54(2), 445-451. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 00336882231168504

Hu, K. (2023). ChatGPT Sets Record for Fastest-Growing User Base: Analyst Note. Reuters. February 2. https://tinyurl.com/4jpfe23e

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. (1999). Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Im, I., Hong, S., & Kang, M. (2011). An International Comparison of Technology Adoption: Testing the UTAUT Model. Information & Management, 48(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2010.09.001

Ivanov, S., & Soliman, M. (2023). Game of Algorithms: ChatGPT Implications for the Future of Tourism Education and Research. Journal of Tourism Futures, 9(2), 214-221. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-02-2023-0038

Ivanov, S., Soliman, M., Tuomi, A., Alkathiri, N., & Al-Alawi, A. (2024). Drivers of Generative AI Adoption in Higher Education through the Lens of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Technology in Society, 77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102521

Kalpokiene, J., & Kalpokas, I. (2023). Creative Encounters of a Posthuman Kind: Anthropocentric Law, Artificial Intelligence, and Art. Technology in Society, 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102197

Khan, M., Al Raja, M., & Al-Shanfari, S. (2019). The Effect of Effort Expectancy, Ubiquity, and Context on Intention to Use Online Applications. Paper presented in the 2019 International Conference on Digitization (ICD), Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, November 18-19.

Khlaif, Z., Ayyoub, A., Hamamra, B., Bensalem, E., Mitwally, M. A., Ayyoub, A., Hattab, M., & Shadid, F. (2024). University Teachers’ Views on the Adoption and Integration of Generative AI Tools for Student Assessment in Higher Education. Education Sciences, 14(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101090

Kline, R. (2023). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford. https://tinyurl.com/4ssfarkm

McLeod, A., Pippin, S., & Mason, R. (2008). Individual Taxpayer Intention to Use Tax Preparation Software: Examining Experience, Trust, and Perceived Risk. Journal of Information Science and Technology, 2(4). https://tinyurl.com/nws5mzrp

Menon, D., & Shilpa, K. (2023). “Chatting with ChatGPT”: Analyzing the Factors Influencing Users’ Intention to Use the Open AI’s ChatGPT using the UTAUT Model. Heliyon, 9(11). https://tinyurl.com/5b6azst9

Mishra, P., Warr, M., & Islam, R. (2023). TPACK in the Age of ChatGPT and Generative AI. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 39(4), 235-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2023.2247480

Mohammed, A., White, G., Wang, X., & Kai Chan, H. (2018). IT Adoption in Social Care: A Study of the Factors that Mediate Technology Adoption. Strategic Change, 27(3), 267-279. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2200

Naujoks, T., Schulte, B., & Hattula, C. (2024). Exploring Perceptions and Usage of Generative Artificial Intelligence: An Empirical Study among Management Studies. In F. Tigre (ed.), Artificial Intelligence, Co-Creation and Creativity: The New Frontier for Innovation (pp. 178-94). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003453901

Ng, K., Drenon, B., Gerken, T., & Cieslak, M. (2025). DeepSeek: The Chinese AI App that Has the World Talking. BBC News. February 4. https://tinyurl.com/3ktwxjzd

Nikitina, I., & Ishchenko, T. (2024). The Impact of AI on Teachers: Support or “Replacement? Scientific Journal of Polonia University, 65(4), 93-99. https://tinyurl.com/35maw8hk

Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. (1994). Psychometric Theory. McGraw-Hill. https://tinyurl.com/26pe6npb

Patil, P., Tamilmani, K., Rana, N., & Raghavan, V. (2020). Understanding Consumer Adoption of Mobile Payment in India: Extending Meta-UTAUT Model with Personal Innovativeness, Anxiety, Trust, and Grievance Redressal. International Journal of Information Management, 54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102144

Pavlou, P. (2003). Consumer Acceptance of Electronic Commerce: Integrating Trust and Risk with the Technology Acceptance Model. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 7(3), 101-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/10864415.2003.11044275

Peres, R., Schreier, M., Schweidel, D., & Sorescu, A. (2023). On ChatGPT and Beyond: How Generative Artificial Intelligence May Affect Research, Teaching, and Practice. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 40(2), 269-275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2023.03.001

Plata, S., De Guzmán, M., & Quesada, A. (2023). Emerging Research and Policy Themes on Academic Integrity in the Age of ChatGPT and Generative AI. Asian Journal of University Education, 19(4), 743-758. https://doi.org/10.24191/ajue.v19i4.24697

Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879-903. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Proctor, M., & Marks, Y. (2013). A Survey of Exemplar Teachers’ Perceptions, Use, and Access of Computer-Based Games and Technology for Classroom Instruction. Computers & Education, 62, 171-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.022

Rahman, M., Ming, T., Baigh, T., & Sarker, M. (2023). Adoption of Artificial Intelligence in Banking Services: An Empirical Analysis. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 18(10), 4270-4300. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-06-2020-0724

Rice, S., Crouse, S., Winter, S., & Rice, C. (2024). The Advantages and Limitations of Using ChatGPT to Enhance Technological Research. Technology in Society, 76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102426

Schaupp, L., Carter, L., & McBride, M. (2010). E-File Adoption: A Study of US Taxpayers’ Intentions. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(4), 636-644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.12.017

Shahzad, M., Xu, S., & Javed, I. (2024). ChatGPT Awareness, Acceptance, and Adoption in Higher Education: The Role of Trust as a Cornerstone. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1). https://tinyurl.com/bdz3kxn2

Teo, T. (2009). Modelling Technology Acceptance in Education: A Study of Pre-Service Teachers. Computers & Education, 52(2), 302-312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2008.08.006

Teo, T., & Milutinovic, V. (2015). Modelling the Intention to Use Technology for Teaching Mathematics among Pre-Service Teachers in Serbia. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 31(4). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1668

Teo, T., & Zhou, M. (2014). Explaining the Intention to Use Technology among University Students: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 26, 124-142. https://tinyurl.com/55kh8evb

Thiesse, F. (2007). RFID, Privacy and the Perception of Risk: A Strategic Framework. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 16(2), 214-232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2007.05.006

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M., Davis, G., & Davis, F. (2003). User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425-478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157-178. https://doi.org/10.2307/41410412

Watermeyer, R., Phipps, L., Lanclos, D., & Knight, C. (2024). Generative AI and the Automating of Academia. Postdigital Science and Education, 6(2), 446-466. https://tinyurl.com/yvsdm5zf

Wong, K., Teo, T., & Russo, S. (2013). Interactive Whiteboard Acceptance: Applicability of the UTAUT Model to Student Teachers. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 22. https://tinyurl.com/ydj6b6jd

Wu, W., Zhang, B., Li, S., & Liu, H. (2022). Exploring Factors of the Willingness to Accept AI-Assisted Learning Environments: An Empirical Investigation Based on the UTAUT Model and Perceived Risk Theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.870777

Yu, C. S. (2012). Factors Affecting Individuals to Adopt Mobile Banking: Empirical Evidence from the UTAUT Model. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 13(2), 104-121. https://tinyurl.com/mwuw6v3k

Zhang, T., Tao, D., Qu, X., Zhang, X., Lin, R., & Zhang, W. (2019). The Roles of Initial Trust and Perceived Risk in Public’s Acceptance of Automated Vehicles. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 98, 207-220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2018.11.018

Zhou, T., Lu, Y., & Wang, B. (2010). Integrating TTF and UTAUT to Explain Mobile Banking User Adoption. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(4), 760-767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.01.013

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contribution to Authorship

Dr Shakeel Iqbal contributed to conceptualisation, research framework, literature review, discussion of results, conclusion and recommendation. Dr Muhammad Naeem Khan contributed to data collection, data curation, analysis, and reporting results

Ethic Statemen

It is stated that the researchers have complied with relevant ethical guidelines, including the treatment of human or animal participants, informed consent, and discipline-specific ethical practices such as the ethical use of artificial intelligence or management of information.

Iqbal, S. & Khan, M. N. (2026). Navigating the New Normal: Faculty Perception of Trust and Risks in Adopting Generative Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education. Revista Andina de Educación 9(1) 6002. Published under license CC BY-NC 4.0