Revista Andina de Educación 7(2) (2024) 000728

The Magical Powers of Trash: An Art and Recycling Experience in Early Childhood Education

Los poderes mágicos de la basura: Una experiencia de arte y reciclaje en educación infantil

Paulina Jara Aguirrea

, David López-Ruizb

, David López-Ruizb

a Universidad de Chile. Postgraduate Degree in Art Therapy Specialization, Art Therapy Mention. Las Encinas 3370, CP 7800020, Santiago, Chile.

b Universidad de Murcia. Department of Plastic, Musical, and Dynamic Expression. Calle Campus Universitario 11, 30100, Murcia, Spain.

Received April 11, 2024. Accepted July 29, 2024. Published October 4, 2024

© 2024 Jara Aguirre & López-Ruiz. CC BY-NC 4.0

https://doi.org/10.32719/26312816.2024.7.2.8

Summary

This proposal seeks to highlight the expressive possibilities of waste materials within the context of an art workshop with a therapeutic focus. These materials offer communicative possibilities that enhance various forms of expression while facilitating symbolic play in specific contexts. The experience occurred over a year with a group of children aged 4 to 6 in a preschool in Viña del Mar, Chile, and focused on two objectives: fostering creative exploration and the expressive possibilities of working with waste materials, and facilitating emotional exploration both with the materials as well as among participants to encourage openness to the emotional world and peer interaction. The chosen methodology was based on exploration and play, with structured individual and group work sessions, using prompts and themes aligned with the prescribed curriculum for this age group. The results highlight the benefits of this type of therapeutic intervention in children, as it strengthens emotional and creative development in the educational context. Equally significant was the involvement of the entire educational community in promoting a culture of recycling and reuse.

Keywords: art therapy, education, art, childhood, recycled materials

Resumen

Esta propuesta busca visibilizar las posibilidades expresivas del material de desecho en el contexto de un taller de arte con enfoque terapéutico. Estos materiales ofrecen posibilidades comunicativas que ponen en valor las diferentes formas de expresión, al tiempo que facilitan el juego simbólico en determinados contextos. La experiencia se desarrolló durante un año, con un grupo de niños y niñas de 4 a 6 años, en una escuela infantil en Viña del Mar, Chile, y se enfocó en dos objetivos: favorecer la exploración creativa y las posibilidades expresivas del trabajo con material de desecho, y permitir la exploración emocional con el material y entre los participantes, para favorecer la apertura al mundo emocional y la interacción entre pares. Se optó por una metodología basada en la exploración y el juego, con sesiones estructuradas de trabajo individual y grupal, consignas y temáticas establecidas en relación con el currículo prescrito para el nivel. Los resultados obtenidos permiten visibilizar los beneficios que este tipo de intervenciones terapéuticas generan en niños y niñas, al fortalecer el desarrollo emocional y creativo en el contexto educativo. Igualmente, es destacable la involucración de toda la comunidad educativa por medio de la cultura del reciclaje y la reutilización.

Palabras clave: arteterapia, educación, arte, infancias, material reciclado

Introduction

This study stems from an understanding of art as a meaningful tool in early childhood education, particularly when considered through the lens of children’s gestural and communicative processes and their interaction with the environment. It is based on the use of art as a necessity during childhood, utilizing recycled materials. Art therapy, which combines artistic practice with therapeutic and psychological approaches, provides an alternative and complementary means of communication to the verbal one, particularly valuable in early stages of education. Additionally, the transfer of values—pedagogical, social, and cultural—through art is vital (Gutiérrez, 2020).

In this context, we sought to implement an art and recycling workshop with a therapeutic focus for children aged 4 to 6. This workshop aimed to explore how this experience influences emotional expression, play, and social interaction through art. For this reason, the research focused on exploring how such workshops impact the various moments of connection between recycled objects and children in an educational setting.

The study was conducted in a private school in Viña del Mar, Chile, where participants attended a weekly one-hour workshop for a school year. The workshop focused on working with waste materials and promoted play, interaction, and emotional expression. Following the principles of art therapy in educational contexts, the creative process was considered more important than the final result. This methodology consisted of weekly sessions where the children worked with various recycled materials, engaging in exercises designed to stimulate their creativity, foster social interaction, and facilitate emotional expression. This approach is based on the premise that art can serve as a powerful vehicle for accessing children’s inner world, allowing them to express thoughts, feelings, and desires symbolically.

The significance of this experience lies in several aspects. First, it explores the potential of art as a therapeutic tool in early childhood education by providing a safe space for emotional expression and non-verbal communication. It also promotes the development of social and emotional skills through play and interaction, contributing to a deeper understanding of how art can be used as an alternative means of communication in early education stages (Gómez Juárez & Especial, 2016).

This research also provides valuable insights into the implementation of art therapy approaches in regular educational contexts, addressing challenges such as teacher training. By focusing on the creative process and the act of making (Dalley, 1984; McDonald & StJ Drey, 2017; McDonald et al., 2019), rather than the final product, the study emphasizes the importance of interpreting children’s artistic productions as a form of communication, recognizing their vulnerability and expressive potential. Ultimately, this work aims to contribute to the fields of early childhood education and art therapy by highlighting how art, combined with the use of recycled materials, can be a powerful tool for children’s emotional and social development, particularly when implemented in a safe and supportive educational environment.

Waste Materials

The diversity and richness of artistic materials used in therapeutic work, especially in the school context, allow for a deepening of various areas of expression for participants, enabling them to gain sensory experiences and evoke memories, as Moon (2010) states. However, it is unconventional materials that offer new creative and aesthetic possibilities for experimenting with unique shapes, textures, and colors. Often, these alternative materials come from unusual sources, such as industrial or domestic waste. By using them, participants can give new life to low-value objects, transforming them into unique creative productions. Additionally, these types of materials can also be more sustainable and environmentally friendly, making them an increasingly popular option for experimentation; thus, they deserve the opportunity to be explored.

Waste materials are a rich resource for classroom projects (Prieto & Ruiz, 2022), while also providing the opportunity to connect with the work of emerging artists who, in a specific historical context, were pioneers in this movement, such as Tony Cragg (1949-), Bruce Conner (1933-2008), Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008), Yves Klein (1928-1962), and Jean Tinguely (1925-1991), among many others.

Broadly speaking, it could be said that the materials considered as waste are those that have had a first life with a specific function and use, but have since lost that function and become trash. These materials are not suitable for refurbishment in order to give them a new life; however, they can become raw materials for new creations. In this context, artistic expression gives these materials a new life. The objects referenced may include paper or plastic bags, plastic bottles and caps, cardboard tubes and rings, lids, boxes, containers of all kinds (polystyrene trays, straws, medicine packaging, cookie and candy boxes, etc.), cardboard, jars, papers... anything that can be considered waste falls within this category of free materials, ideal for classroom use.

It is important to make a distinction between waste materials and waste objects, as they carry different symbolic meanings. A waste object is understood as an element used in a manner inconsistent with its function, form, meaning, or intended use. Artistic expressions influenced by movements generated during the Second Avant-Garde (1945-1970) greatly nurtured artists, allowing them to become aware of the use of materials around them in relation to form, color, texture, etc., to produce art (Echarri, 2022). We will also distinguish between waste materials and recycled materials. While waste materials are elements discarded and potentially turned into raw materials, recycled materials have already been transformed and recovered after being discarded. This is the case with recycled paper, cardboard, or plastic, which we can buy in a store or which are used to manufacture new items.

In this sense, it is essential to understand the difference between recycling and reusing. While both concepts allow objects to be given new life, the symbolic meanings of each are different. For this reason, works that emerge from waste materials are truly important within the art therapy framework, as they offer possibilities for transformation and the symbolism that may arise from them.

Although there are many materials that can be used in art therapy and artistic education, working through recycling opens a window of possibilities for re-signification and change. The creative process with this medium initiates profound transformations and restoration in those who engage in the proposed activity, leading to ‘a shift from a prior state (use-discard), to a constructive present (recycling and reworking), and ultimately to a transformed outcome’ (López Ruiz, 2015, p. 121). As in other experiences, different communicative possibilities open up for expression.

The materials we tend to discard, due to their lack of cost and proximity, provide the perfect opportunity to engage in any artistic activity freely, without fear of mistakes or failure. Having these types of materials often helps reduce the anxiety associated with artistic activity since, not being tied to the knowledge of a specific technique, those who work with them are more likely to tolerate potential frustrations. For all these reasons, the use of waste materials as a medium enables creative processes to go beyond strictly academic settings and become activities where both exploration and play take on a central role.

Given that the materials in question are obtained through collection rather than purchase, searching for them also offers the opportunity to generate a sense of collectivity by involving the group with whom one is working. This is particularly effective when working with socially vulnerable people or groups, such as community and social centers, educational institutions, hospitals, or other locations on the outskirts of cities. Additionally, during the collection and search for materials, symbolic bonds are often formed with the environment and the neighborhood where the intervention takes place (McNiff, 2011). Another characteristic of this type of material is the lack of visual appeal typically associated with it, simply because it is considered trash. However, for those who use it for their work, it is precisely the assimilation and approach to it that can connect them and invite exploration and limitless transformation. These individuals are always aware that even small changes or transformations they make will be significant to the material. In most cases, this act leads to reflection and advancement in the process of constructing the work.

As mentioned earlier, working with recycled materials does not require technique or a specific intervention. The process involves joining, tearing, gluing, assembling, painting, etc., different elements that, together, contribute to the creation of a particular object with personal and specific symbolism. It is true that, through the activities carried out, it has been observed that using this method contributes to the improvement and strengthening of participants’ self-esteem and enables the development of numerous artistic interventions, through different solutions, possibilities, and variations.

In summary, working with waste materials encourages creative processes and improves individuals’ concentration abilities. The forms already inherent in the material allow for creative imagining and stimulation of solutions, eliminating barriers that other media might pose. Additionally, in this creative process, the capacity for internal analysis gives individuals total freedom to express themselves, enabling them to create one or more works that evolve over the sessions.

Ultimately, as López Ruiz (2015, p. 122) states: “The use of waste materials allows for reinterpreting trash through recycling and transforming it into a raw material for a work that is often different and aesthetically more beautiful than the original object. By working with waste materials in therapy, we allow ourselves a new way of seeing and feeling, developing the ability to discover the original potential of that object. Ultimately, it is this reflection on potential that enables the creative act to contribute to restoration and recycling.”

The Art and Recycling Workshop with a Therapeutic Focus in the Preschool Educational Context

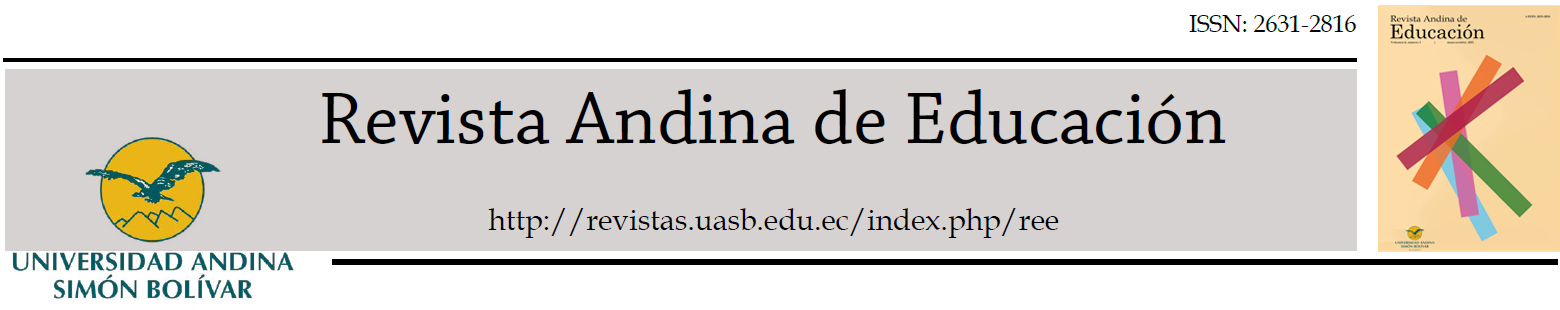

The experience developed (figure 1) is based on the idea that artistic activities and play for preschool-aged children are tools that allow for the exploration of the world and the adequate development of their potential. These early experiences and approaches to the world will likely influence and shape not only the development of their brains but also their emotional world. It is at this stage of development that sensory stimulation, the development of experiences that build confidence, and exploration of the world with their own bodies take on greater importance in learning. As Gómez Arango and Parra (2011) mention, with each new experience a child has, new and increasingly complex neural connections are formed, strengthening the ones that already exist. Thus, the art workshop with a therapeutic focus is conceived as an exploratory space where participants can gain diverse experiences related both to plastic expression and the emotional world. It is interesting to think of this creative space as one that coexists with the school’s pedagogical curriculum.

Fig. 1. Presentation of the experience.

Source: Authors (2024).

The arts are the type of activities that stimulate and develop various capacities in people, mainly because they are explored and experienced through the entire body. This allows for the stimulation of sensory capacities related to sensory exploration and psychomotor abilities, which enable a bodily-muscular response to the sensations experienced. Additionally, it encourages cognitive skills for analysis, reflection, planning, and decision-making, as well as for finding various ways to solve problems and learn from them. Finally, it sharpens the affective capacity to open up to the emotional world and its competencies: knowing, recognizing, naming, modulating one’s own emotions, and providing emotional support to others (Cassasus, 2007).

The art workshop with a therapeutic focus was conducted in a preschool in the city of Viña del Mar, with children aged 4 to 6 years old. It was organized as a weekly one-hour session within the school program, in which each group of participants could explore through play and manipulation with various materials. The groups consisted of eight to fifteen children. Each session was guided by an art therapist, accompanied by a teacher or teaching assistant. The art therapist’s role was to propose activities and guide the sessions, while the teacher’s and assistant’s role was mainly to address practical matters, such as helping the children wash their hands, glue objects with hot glue, or escort them to the bathroom. However, they also played a fundamental role in modeling behaviors and mediating group dynamics.

The idea of group work was to allow for experimentation and play. As Oaklander (2023) mentions, from a therapeutic standpoint, the group becomes a laboratory where new behaviors can be safely tested thanks to the therapist’s support. In the group setting, it becomes possible to get to know oneself through interaction with others and thus expand behavioral repertoires. The benefits of a therapeutic space also extend to children’s social development. Group activities within these spaces foster positive social interaction, where essential skills such as cooperation, mutual respect, and conflict resolution are learned. These social skills are crucial not only for academic success but also for general well-being and the ability to form healthy relationships throughout life.

During this experience, the emphasis was placed on working with discarded materials as an expressive means accessible to the participants, allowing them to collaborate in sourcing materials from home. Despite having other materials available, the decision to use discarded items aimed to foster a fear-free approach to transforming and experimenting with volumes and shapes without the participants needing to craft them specially.

Between March and December, weekly group sessions were held, allowing participants to play and express themselves through plastic creation. A workshop with directed instructions was chosen to reduce the anxiety some children felt when facing a wide variety of materials and a blank canvas. Each month, a different theme related to the classroom’s teaching unit was explored, connecting to each grade’s curriculum.

Context and Participants

The preschool where the experience took place is located in Viña del Mar, Chile. It is a private school in the city center, with an average of twenty students per level. The classrooms are open spaces with plenty of natural light and attached bathrooms. There are also furniture units available for storing materials and preserving completed works. The workshop was held in each group’s classroom, accessible from inside the building but also connected by glass doors to the central courtyard, which features vegetation and play equipment.

Groups were divided by age: the first group comprised 4-year-old children, while the second group included 5- and 6-year-olds. This natural division was made to ensure that the proposed activities aligned with each group’s skills and interests. Given these characteristics, sessions were designed so activities could start and finish within the same hour. Another consideration was the time each group could focus: the 4-year-olds could maintain attention for 30 minutes, while the 5- and 6-year-olds managed for about 45 minutes.

The 4-year-old group consisted of thirteen participants, six girls and seven boys. The 5- and 6-year-old group had twelve participants, eight girls and four boys.

The art and recycling workshop with a therapeutic focus was created by the school administration in collaboration with the teachers to promote protective factors for childhood, such as self-esteem, self-image, frustration tolerance, play, creativity, interaction with others, emotional education, and both verbal and non-verbal expression. It was precisely this perspective that gave the workshop its therapeutic focus.

Goals and Sessions

After the first meeting with the school administration and teachers of each group, an observational approach was taken to assess the participants’ skills with art materials. Children were invited to freely create with available materials in the classroom, including colored pencils, markers, wax crayons, clay, various types of paper, tempera, brushes, rollers, scissors, pipe cleaners, and foam rubber.

Since most children opted to use pencils and markers, discarded materials were introduced as a way to encourage new forms of creation. The following goals were established:

- Main Objective: To highlight the therapeutic potential of art as a tool in children’s emotional processes within an educational context.

- Secondary Objective 1: To use discarded materials as a means of exploration through different forms of creative expression.

- •Secondary Objective 2: To promote symbolic play through their own plastic creations.

- Secondary Objective 3: To develop emotional competencies through artistic expression.

To achieve these goals, it was proposed that the art and recycling workshop with a therapeutic focus would allow participants to acquire knowledge about recycling, while their creations would help them explore the emotional world, play, and interact with peers. Activities were designed to connect the school’s annual teaching units with the stated objectives.

Semi-directive sessions were structured with an opening activity for exploring discarded materials, a development activity focused on creating with those materials, and a closing activity that promoted both verbal and non-verbal expression among participants, the therapist, and the teacher/assistant.

Each session began with a greeting and exploration of suggested discarded materials for about ten minutes. This time allowed each participant to explore the objects freely, sometimes being encouraged to make sounds with the material, listen or look through it, build a structure, or simply observe and describe it verbally.

The development activity was always structured and guided toward a work objective, although the outcomes and ways to achieve them were diverse, always respecting each participant’s choices. For example, if the activity was to make a puppet, each participant could add elements or modify their creation according to their own expressive interests, but the result would always be their personal interpretation of the puppet. The proposed activities aimed to guide participants in creating objects that could be used later inside or outside the workshop. It is important to note that the creations did not necessarily have an aesthetic purpose but rather an expressive one.

Sessions typically ended with a free activity, although sometimes this was intentional. These activities included body and play, such as puppet shows, carnivals, dances, games using the sound and the wind, or role-playing. This encouraged participants to enjoy the creative process and opened opportunities for exploration with others in various contexts.

Overall, the proposed activities were interesting in terms of experience and how participants engaged with the material, their work, and play. However, some activities opened doors to deeper emotional exploration and embodied images.

Some Proposed Activities

The workshop was planned for approximately 30 weeks of work, during which at least 27 different activities were carried out. Out of these, four activities are particularly noteworthy due to their impact on the participants.

Masks (Group of 5- and 6-Year-Olds)

The mask session began with an introduction to the concept and purpose of masks. The children observed images of different tribes, communities, and artistic expressions that use masks. They were encouraged to notice specific details and characteristics of each one.

After the introductory activity, the children were invited to observe the materials available on the table, including egg cartons, magazine paper, vibrant-colored tissue paper, and glue. Each participant could explore how to construct their mask, starting by feeling the egg carton on their face and looking through the eye holes. This allowed each child to intuitively adopt a character or way of being in the space. After exploring the material, they were invited to tear pieces of magazine and colored paper with their hands, forming pieces that could be curled at one end to resemble feathers. Tearing the paper opened a space for the children to talk about how the sensation felt in their hands and ears.

Next, they prepared feathers with the torn paper and were invited to create their own masks. This process was completed relatively quickly, and much of the conversation centered around how the masks reminded them of a carnival, drawing a parallel between the feathers and the Rio de Janeiro Carnival. Therefore, after finishing the masks, they were invited to wear them. To close the session, they embraced the carnival idea and were invited to dance and interact with their masks to the rhythm of samba. The carnival moment was interesting because they interacted not only with each other in the classroom but also outside in the courtyard, inviting other children to dance.

Fig. 2. Masks created by children aged 5 and 6.

Source: Authors (2024).

Puppets (4-year-old group)

The puppet session was carried out with both groups. However, for the 4-year-old group, the activity marked an opportunity to create stories and engage in role-playing over several sessions. It started by exploring different shapes and sizes of boxes, mainly medicine and tea boxes, which were initially observed in their original use as containers. Then, they explored their volume and the constructive possibilities it allowed. Each participant then chose a box that would allow them to insert their hand and manipulate it. At this point, the concept of a character was introduced, though it was initially only visualized by each participant. A variety of materials were available on a table, including pieces of colored and magazine paper, buttons, yarn in different colors, twigs, plastic bottle caps and lids, and glue. Additionally, colored pom-poms and sequins were provided.

The time spent making the puppet was brief, approximately ten minutes, and required minimal adult assistance. After creating the puppet, participants were encouraged to interact with each other through their puppet characters. This led to interesting dialogues that later turned into shared stories. The puppet served as a mediator for verbal dialogue and interaction between participants. In subsequent sessions, the puppets were used again to create stories and improvisational plays based on interaction.

Fig. 3. Puppets made from medicine boxes, later used for a puppet show.

Source: Authors (2024).

Stories in Matchboxes (5- and 6-year-old group)

In this session, the narrative served as the central theme. The initial activity focused on observing images or photographs cut out from magazines, depicting various scenes, people, and actions. Participants were invited to interpret the images, describing what they saw. The discussion was guided to encourage each person to share what they thought was happening and identify the specific parts of the image where these details could be seen, as a way to foster attention to detail.

Afterward, they were shown an example of a visual story created in a matchbox, resembling a small book, and the same image-reading exercise was repeated. Together, they came up with a title for that story. On the table, there were pencils and markers, sheets of white paper cut and folded to fit the size of the box, matchboxes covered with white adhesive paper, and glue sticks. Participants were then encouraged to create their own visual story. The creative activity focused on drawing and coloring the scenes of the story so that the matchbox would serve as the cover. To conclude the activity, the group sat in a circle, and each child took turns sharing their story for the others to read. An interesting aspect of this moment was that the children realized there wasn’t just one way to interpret their stories, and sometimes the story someone else read was different from the one they had drawn.

Fig. 4. Some stories created in matchboxes.

Source: Authors (2024).

Magic Wands (4-year-old group)

The activities proposed throughout the course ranged from the concrete to the abstract. However, it was also important to incorporate magical thinking as a way for the children to construct their own reality through symbols. Thus, the idea of magic wands was introduced as objects that symbolically hold power. The activity focused on exploring the desires each participant had, not in the material realm, but in the emotional one.

On the worktable, the following materials were laid out: pieces of cardboard cut into circular and oval shapes, plastic lids and caps, pieces of colored tissue paper, foam circles in various sizes and colors, magazine clippings, white glue, and adhesive tape.

The exercise began with a focus on centering the body through breathing, and the children were encouraged to imagine an object that had the power to fulfill a dream. They were invited to envision a wand with magical powers. After this visualization, the materials were placed on the tables, and the children were encouraged to create their own magic wands freely. For this activity, the group was divided into two tables to provide more space for working and to promote observation among them during the creative process. The magic wands created by the participants at the same table looked similar to each other, although it later became evident that the intention behind each one was different. Once all the wands were ready, the group gathered in a circle to share the power or magic of their wands. The situation was modeled so that the powers would be related to immaterial and/or emotional things or situations. As a result, powers such as ‘spending more time with my parents,’ ‘enjoying nature,’ or ‘laughing,’ among others, emerged. Once everyone shared the power of their wands, the therapist gathered them in the center of the circle, as if to truly infuse them with the power each child had given.

After this exercise, the participants had time to play freely with their creations in the schoolyard. It was interesting to see that, at that moment, some of them began to ask questions about the power they had attributed to their wands. This spontaneous reflection led to shared experiences and connections among them.

Fig. 5. Moment when children shared the powers of their magic wands.

Source: Authors (2024).

Documenting the Experience

During the school year, and considering the importance of developing a workshop of this nature with children, it was decided to document the process. Two tools were used for this purpose. On the one hand, field journals were kept for each level, and in addition, images and videos were collected documenting the artistic creation process, the games, and the interactions among the participants.

The field journals were structured to reflect the proposed plan for each daily activity. This plan included an introductory activity, a development activity, and a closing activity, detailing the materials to be used. The journals then recorded interactions, findings, and relevant comments from the participants that emerged during the session, as well as a narrative of what happened and what the workshop facilitator found interesting. After each session, brief meetings were held with the teachers to discuss comments, suggestions, and insights, which were also recorded in the field journals.

Both during and after the sessions, photographs and videos were taken to document the creative process, showing both the exploration of waste materials and the final artwork. Fragments of the session were also recorded, capturing interesting interactions related to individual and collective play, theater performances, installation-type interventions in the playground, and manipulation of objects.

It is important to clarify that the documentation of the experience was not intended as research, but rather as a way to systematize the work done to replicate the experience in other preschools in the region. For this reason, this article does not delve into a research methodology.

Discussion

The art and recycling workshop with a therapeutic focus lasted approximately 30 weeks in the preschool education context. It provided various opportunities for children, mainly in learning to express themselves through a universal language like art. The group became a safe space where children could experiment not only with materials but also with new or different behaviors (Oaklander, 2023). This provided a valuable experience in using art as a tool for emotional and creative development. The use of discarded materials in an educational context was explored with various elements, noted for their accessibility and the creative possibilities they offered. Family involvement in collecting materials played a crucial role, engaging the entire community in the creative process and raising awareness about the importance of recycling and reusing resources. This enabled both adults and children to recognize the creative potential in materials previously regarded as trash.

The accessibility of discarded materials and the ability to continuously obtain them enabled children to explore without fear of making mistakes, fostering an attitude of experimentation and discovery. Using materials with pre-established volumes, such as boxes, cardboard tubes, bottles, and lids, provided a solid foundation for creating three-dimensional works and led to the development of more complex and stimulating projects. In terms of manipulating these materials, the importance of preparing some of them beforehand was noted to facilitate their use. White glue was the primary adhesive used, although hot glue guns, handled only by adults, were occasionally used to speed up certain processes. The sessions, which combined material exploration, plastic activity, play, and body expression, allowed the creations to take on meaning beyond the experience with discarded materials or the creation of plastic works. These activities promoted playful expression, social interaction, and the development of emotional skills.

Conclusions

The workshop effectively demonstrated the therapeutic potential of art in supporting children’s emotional processes. Through artistic exploration and creation, the participants were able to channel their emotions, express themselves freely, and develop greater self-awareness and awareness of their surroundings. Activities such as mask-making, puppets, and stories in matchboxes promoted symbolic and verbal interaction among the children, while also creating spaces of trust and credibility (Oaklander, 2023). The reimagining of discarded materials into play objects allowed the children to explore new forms of interaction and communication, enriching their educational and emotional experiences. The structure of the sessions, which combined material exploration, artistic activity, play, and body expression, allowed the children to connect with themselves and express themselves in a safe and creative way (Cassasus, 2007).

The active participation of families in gathering materials and collaborating in the creative process strengthened the connection between home and school, fostering a culture of support and cooperation. This approach enriched the educational experience by allowing children to develop emotional competencies and social skills through artistic expression. In conclusion, the art and recycling workshop, initially designed to raise awareness about recycling, became a space full of learning for the entire school community. As Mediavilla (2021) suggests, the contribution of art in early childhood education lies in enabling the knowledge of the world and oneself. This workshop proved to be a powerful tool for children’s emotional and creative development in an educational context, promoting a culture of recycling and reuse and enhancing the overall educational experience.

References

Cassasus, J. (2007). La educación del ser emocional. Cuarto Propio/Espacio Indigo. https://tinyurl.com/yc2p8hnm

Dalley, T. (ed.) (1984). Art as Therapy: An Introduction to the Use of Art as a Therapeutic Technique. Routledge. https://tinyurl.com/4fnz592b

Echarri, F. (2022). El programa QuidArte del Museo Universidad de Navarra: El arte al servicio del bienestar y el cuidado en el contexto de la pandemia COVID-19. Arteterapia, 17, 71-84. https://tinyurl.com/45c9nv5d

Gómez Arango, A., & Parra, D. (2011). Creatividad para padres. Norma. https://tinyurl.com/je8d43nv

Gómez Juárez, M., & Especial, E. (2016). Arteterapia y autismo: El desarrollo del arte en la escuela. Publicaciones Didácticas, 69(1), 31-48. https://tinyurl.com/ff35zdad

Gutiérrez, E. (2020). El proceso de creación plástica en la formación del profesorado de educación infantil y primaria: Metodologías prácticas para la reflexión en educación artística. Observar, 14, 63-88. https://tinyurl.com/yckh4yfb

López Ruiz, D. (2015). Estudio general del uso y aplicación de materiales artísticos en el contexto arteterapéutico español [Doctoral thesis]. Universidad de Murcia, España. https://tinyurl.com/4a55s7au

McDonald, A., Holttum, S., & StJ Drey, N. (2019). Primary- School-Based Art Therapy: Exploratory Study of Changes in Children’s Social, Emotional and Mental Health. International Journal of Art Therapy, 24(3), 125-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2019.1634115

McDonald, A., & StJ Drey, N. (2017). Primary-School-Based Art Therapy: A Review of Controlled Studies. International Journal of Art Therapy, 23(1), 33-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2017.1338741

McNiff, S. (2011). From the Studio to the World: How Expressive Arts Therapy Can Help Further Social Chan- ge. En E. Levine y S. Levine (eds.), Art in Action: Expressive Arts Therapy and Social Change (pp. 78-92). Jessica Kingsley Publishers. https://tinyurl.com/43typp5m

Mediavilla, E. (2021). Construcciones del cuerpo y las ar- tes para una educación infantil transformadora. Artete- rapia, 15, 23-32. https://tinyurl.com/4dx8ab67

Moon, C. (2010). Theorizing Materiality in Art Therapy: Negotiated Meanings. En C. Moon (ed.), Materials & Media in Art Therapy: Critical Understandings of Diver- se Artistic Vocabularies (pp. 49-88). Routledge. https://tinyurl.com/2zrw47au

Prieto, J., & Ruiz, V. (2022). Transformando los desperdicios en arte participativo: Trash art + Patrimonio. ANIAV. Revista de Investigación en Artes Visuales, 10, 59-72. https://doi.org/10.4995/aniav.2022.17238

Oaklander, V. (2023). El tesoro escondido: La vida interior de niños y adolescentes. Pax. https://tinyurl.com/ybp5vwez Prieto, J., & Ruiz, V. (2022). Transformando los desperdicios en arte participativo: Trash art + Patrimonio.ANIAV. Revista de Investigación en Artes Visuales, 10, 59-72. https://doi.org/10.4995/aniav.2022.17238

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contribution Statement

Paulina Jara Aguirre and David López-Ruiz carried out the writing, data analysis, and critical review of the intellectual content, as well as the theoretical framework and content design. The practical experience, however, was conducted entirely by Paulina Jara Aguirre at a preschool in the city of Viña del Mar.

Ethics Statement

The research work “The Magical Powers of Trash: An Art and Recycling Experience in Early Childhood Education” involved people. For this reason, the authors declare that they respected ethical aspects of working with young children, whose school and guardians were fully informed about the activities carried out in the art workshops and gave their voluntary and informed consent to participate in the experience. Since this was a systematized experience in an educational context and did not involve external research, no participant selection was made, and all students at each level were included. This work is presented as an experience in art, art therapy, and recycling within early childhood education, and seeks to set a precedent for future exploration of art therapy in early childhood education.

Copyright: © 2024 Jara Aguirre & López-Ruiz. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction by any means, as long as it is not for commercial purposes and the original work is properly cited.

Jara Aguirre & López-Ruiz. (2024).The Magical Powers of Trash: An Art and Recycling Experience in Early Childhood Education. Revista Andina de Educación 7(2), 000728. Published under license CC BY-NC 4.0