Revista Andina de Educación 6(2) (2023) 000623

Educating in Exceptional Times: Educational Institutions Management in the Post-Pandemic Era, a Qualitative Study in Mexico Schools

Educar en tiempos extraordinarios: Dirigir instituciones educativas en pospandemia, un estudio cualitativo en escuelas de México

Claudia Fabiola Ortega Barbaa

, Mónica del Carmen Meza Mejíaa

, Mónica del Carmen Meza Mejíaa

, José Francisco Cobela Vargasa

, José Francisco Cobela Vargasa

a Universidad Panamericana Ciudad de México. Escuela de Pedagogía. Augusto Rodin 498, Insurgentes Mixcoac, Benito Juárez, 03920, Ciudad de México, México.

Received January 10, 2023. Accepted March 6, 2023. Published May 02, 2023

© 2023 Ortega-Barba, Meza-Mejía, & Cobela-Vargas. CC BY-NC 4.0

https://doi.org/10.32719/26312816.2023.6.2.3

Abstract

The relevance of managerial action within the school system became evident during the crisis emerged due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The purpose of this research is to share the experiences of school managing directors when trying to meet the needs caused by the crisis. A qualitative and comparative approach was conducted integrating the principles of symbolic interactionism, using focus groups as a gathering information technique, and the ladder of inference analysis. The study concluded that the impact was different in each school due to unique and diverse circumstances, and thus, the strategies adopted by directors responded to their own reality. Traditional institutions found it more difficult to deal with the crisis, while versatile organizations were able to adapt more effectively to the new remote learning ecosystem.

Keywords: school organization and management, private education, educational management, organizational change, qualitative research

Resumen

La relevancia que la acción directiva tiene dentro del sistema escolar se hizo patente en la crisis causada por el COVID-19. Esta investigación tiene como propósito mostrar las vivencias de directivos para atender a las necesidades a causa de la crisis. Para lograrlo se utilizó el enfoque cualitativo y comparativo, integrando los principios del interaccionismo simbólico. Para la recolección de la información se utilizaron grupos focales y, para su análisis, el método de la escalera de la inferencia. Se concluye que el impacto en las escuelas fue diferente, debido a las condiciones de cada una. Así, las estrategias emprendidas por los directivos atendieron a la propia realidad. En las instituciones convencionales se presentaron mayores dificultades para enfrentar la crisis, mientras que las organizaciones versátiles pudieron adaptarse al nuevo ecosistema de aprendizaje remoto con mayor eficacia.

Palabras clave: organización y gestión escolar, educación privada, gestión educativa, cambio organizacional, investigación cualitativa

Introduction

In recent years, research have proved the impact that school managing directors may have in the improvement of educational processes and results (González Fernández et al., 2020; García Aretio, 2021; Pérez et al., 2021; Cárdenas et al., 2022; Meza et al., 2022; Valdivia & Noguera, 2022). Moreover, managerial action had a clear role within the school system in the context of crisis derived from COVID-19 pandemic, with the outstanding effort of school directors to provide a quality education adjusted to the current needs.

In the case of Mexico, where this research was conducted, since the closure of schools centers as preventive action —with the subsequent economic and social consequences (CEPAL, 2020)—, the educational ecosystem entered in a state of emergency and uncertainty (Caputo & Pérez, 2021). From the first quarter of 2020, educational institutions raised several questions, such as: How to guarantee learning continutity?, How to offer technological mediations and experiences to make it possible? How to enable educational agents to achieve an effective performance in virtual environments?

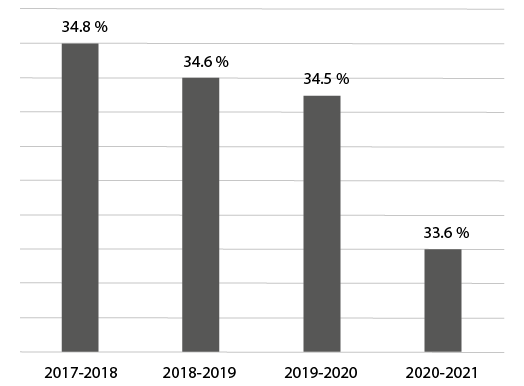

Official data in Mexico show the impact of the pandemic in the educational system: from the year 2018-2019 to 2020-2021 there was a million students less, equivalent to 2.9 %, as illustrated in Figure 1. Studies as the one by Pachay and Rodríguez (2021) and Martínez (2020) connect the influence of the pandemic on school dropout with inequality. More specifically, the main reasons for education dropout were related to the havoc created by the pandemic, according to a national survey on the impact of the pandemic in Education, Encuesta para la Medición del Impacto COVID-19 en la Educación (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, 2021, p. 10).

Fig. 1. National enrollment in primary, secondary, and high school.

Source: Secretaría de Educación Pública —SEP— (2023).

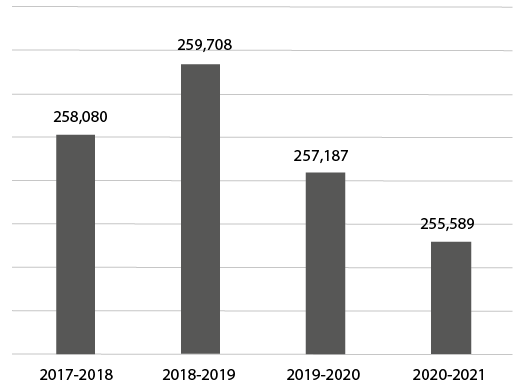

On the other hand, Figure 2 shows a decrease in the number of schools between the years 2018-2019 and 2020-2021: 4,119 educational centers, equivalent to 1.6 %. These schools that could not continue offering their educational service due to lack of resources or support networks closed permanently, as pointed out by Ruiz (2020).

Fig. 2. Number of national primary, secondary and high education schools.

Source: SEP (2023).

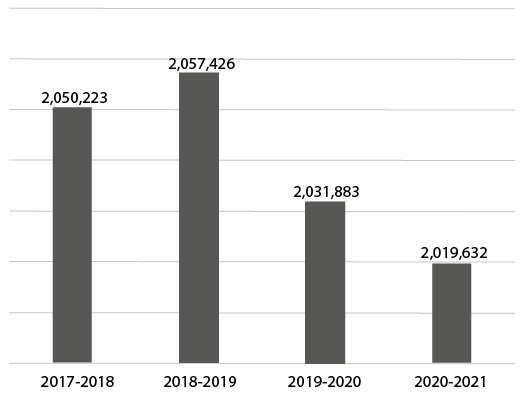

Figure 3 shows the dropout rate of teachers during the pandemic. In this case, the data reflect a decrease in the number of teachers: 37,794 less (1.9 %), mainly due to depression, stress, and physical and mental weariness (Dos Santos et al., 2020; Cortés, 2021).

Fig. 3. Teachers of primary, secondary, and high school education nationwide.

Source: SEP (2023).

Educational institutions depending on their own resources were the more impacted by the health crisis: during the school year 2020-2021, 90 % of the students were enrolled in public institutions and 10 % in private ones. The population who abandoned their studies due to the COVID-19 pandemic or lack of resources who attended the previous year (2019-2020) was 5.4 % from public centers and 7.3 % from private ones. It must also be pointed out that of the total the population inscribed in schools during the years 2019-2020 and 2020-2021, 1 % changed from private to public and 0.9 % from public to private (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, 2021, p. 17).

The evolution of the educational ecosystem is still uncertain. Emerging challenges come into play to alter the normal reality. School directors have a substantive role to organize and supervise all the necessary process to ensure a quality education in adverse times, bearing in mind that the success of managerial work is determined by the level of organization attained (Ramírez et al., 2020; Castellanos et al., 2022) as well as the internal dynamic generated in the institution, “the more visible aspect of the managerial process” (Fuentes, 2015, p. 4). Therefore, an adequate management is essential for the efficient organizational functioning.

Among the literature of the total current challenges, it could be highlighted those works focused on the way educational institutions tried to adapt themselves to the new context. Some of them examined the institution itself (González Calvo et al., 2020; Guerrero et al., 2020), others focused on the teachers and students (Gajardo et al., 2020; González Jaimes et al., 2020; Picón et al., 2020), others on different processes (Bautista et al., 2020; De Vicenzi, 2020; Herrera et al., 2020), or on technology and technological competences (Picón et al., 2020; Sandoval, 2020), but not so many in the management process or the role of the director as head of the educational institution who takes the responsibility of facing such an extreme situation as the one experienced at that moment (Hernández, 2020; Keleş et al., 2020).

Management in the educational sphere has a specific, multidisciplinary field of study “in full process of resizing” (Fuentes, 2015, p. 4) within the comprehensive study of school organization, understanding the latter as the “optimum operation of the institution to achieve its objectives, applying all the available resources rationally employed” (p. 3). Thus, this work focuses on the role of managers and how they conducted the institution processes during the pandemic. In this sense, the following research question arose: How was the managerial experience in the educational institutions to manage the crisis derived from the closure of school centers in the pandemic? The related objective was to present the experiences of managers when attending the needs derived from the situation of crisis.

In the context of Mexico, in the last educational reforms the figure of the school director is emphasized as the main agent to accomplish the institutional change needed in the 21st century. In fact, according to Fullan (2016), school management is the second most important factor, after the teaching staff, regarding the influence on student learning besides being a key tool in the institution core: this figure is expected to provide a management which takes care of the center, the integration and well-being of community members, the requirements from authorities, and report back with results no matter the degree of personal or professional competence, the location of the school, the type of institution, its educational level, or the profile of the community attending. Fullan argues that an efficient management: 1. Establishes and communicates objectives and expectations; 2. Strategically endows with resources; 3. Guarantees quality teaching; 4. Supervises and leads the professional growth of teaching staff and other agents 5. Guarantees a secure ordered environment; and 6. Puts forward the team above himself/herself.

In order to achieve this, the manager has to attain the expected results, solve complex problems, and generate trusting relations which consolidate not just the human capital —in terms of teaching agents within a school—but also a social capital which expresses the quality of interactions and relationships towards a common goal, generally manifested in the institutional mission and vision. In this sense, Fullan (2016) highlights the need of operating following a strategy and knowing to lead facing the uncertain and ambiguous, as this will facilitate the steps needed to reach the objectives and in critical moments random actions and improvised decisions will be avoided, thus evading the worse solutions.

Another aspect to consider in the managerial action is that related to the type of institution. According to Martín-Moreno (2004 and 2007b), educational institutions are complex organizations because they integrate multiple perspectives. In addition, the environments surrounding the school centers are so diverse that the “organizational strategies designed for one or several of these institutions are not often adequate to be applied uniformly to the rest, even if they are covering the same educational levels”. (Martín-Moreno, 2007a, p. 417). To that effect, it is also important the capacity for response of the institution to the requirements that society demands from the organizational model, where institutional decisions and actions are envisioned. In this sense, there are two major, opposing and comparable organizational models: the traditional one and the versatile. The versatile educational center is characterized by its adaptability, flexibility, and compatibility of the structures it hosts, which allows to modify in a coherent, pedagogical way its own configuration to integrate, create, or eliminate different approaches of its organizational parameters according to the environment evolving. Thus, versatile institutions

… transcend the simple flexibility because their structure allows part or full change and reorientation of their organizational formulas towards innovation and new requirements of the socioeducational models they chose to follow. (p. 427)

Contrarily, traditional educational organizations tend to be inward-looking institutions unable to offer a quick response to the context requirements, mainly due to the control and hierarchy guiding their actions. Obviously the transition from a traditional educational center into a versatile one is not an easy task, even less if there is resistance to change in the organizational parameters and in a major sector of the teachers and management teams (Martín-Moreno, 2007a). Likewise, it is clear that the culture of each educational institution reflects the adversities and opportunities faced by the players involved in the generation of successful educational processes. Alleviate resistance to change and existent tensions require a managerial action both committed to quality and professional growth and to the well-being of the people under this leadership.

However, no matter the type of organization, traditional or versatile, “the experiences lived in this difficult times have provided valuable insight and learnings, but it is necessary to capitalize the lessons learned to transform them into opportunities that should not be missed.” (Kochen, 2020, p. 13).

Methodology

As mentioned by Mieles et al. (2012), the complexity derived form the study of the different manifestations of the social and human reality implies a deep reflection on the epistemological principles most adequate to the specific characteristics of human nature. This is why this study uses a qualitative and comparative approach, as the former considers the subjective meanings and the context where the phenomenon takes place (Vega et al., 2014), while the latter contrasts and enables the reflection on the right understanding or interpretation of human matters in specific sociocultural contexts. In other words it allows to achieve a better understanding of the studied phenomenon: the experiences of school directors during the pandemic.

Qualitative research […] pursues the subjective and intersubjective reality as a field of knowledge, ordinary life as an essential scenario for research, dialogue as a possibility for interaction, and thus it incorporates multidimensionality, diversity, and dynamism, as characteristics of people and societies. (Mieles et al., 2012, p. 197)

Understanding dialogue as a possibility for interaction means integrating principles of the symbolic interactionism, as the experience is shaped by situations and the interiorization of the structure of a social network of communications. This means that thought is mediated by cognitive and moral symbols of a significance community (Collins, 2009) from which derives different methods and techniques of information gathering and analysis “that intend to explain complex realities such as feelings, emotions, perceptions, human action meanings, etc.” (Mieles et al., 2012, p. 197). Specifically, the present work used focus groups (Daniel et al., 2013) for information gathering and the Ladder of Inference (Argyris, 1999) for the process of analysis.

Techniques and tools for information gathering

In the context of qualitative research, focus groups are a method to collect data which allows to gather sample participants with a specific purpose and detailed planning to learn about their views (Morgan, 1997; Krueger, 2002; Barbour, 2018). Through this strategy, a guided discussion was organized around a series of open questions in order to obtain substantial information which allowed participants to comprehensively express the situation they were experiencing and how they were coping (Table 1).

Table 1. Trigger questions in focus groups.

|

Objectives |

Trigger questions |

Themes |

|

Knowing the challenges faced by managers when switching from on-site to remote work. |

Which are the challenges faced as manager of an educational institution during the pandemic? |

Challenges in the academic and administrative spheres and the relationship of agents of the educational community. |

|

Identifying the intervention strategies for the operation of the institution in an uncertain environment. |

Which measures have been applied to guarantee the educational model and quality in this particular center? |

Actions to continue the educational service. |

|

Revealing the practices which proved to be innovative and should continue after the pandemic. |

Which measures must prevail within the educational institutions once the pandemic is over? |

Innovation in processes, resources, and policies. |

|

|

|

|

Source: Authors (2023).

The objective of focus groups was to listen and gather information to understand better the experiences of people who lived this moment. In this sense, this method implies several individual interviews which take place at the same time.

Contextualization and participants

In order to plan the focus groups, it was considered that possible participants could be postgraduate students of specializing in Education Management, which requires as admission profile being current school directors. Thus, an open invitation was extended to those students, who agreed to voluntarily participate in the study, sharing their experiences as managers in the uncertain context as the one lived during the pandemic, after school closure. Sample was non-random, specifically based on the following criteria: 1. Currently exercise as school directive, and 2. Being the head of institutions of different educational levels (from preschool to high school), members of the Mexican Secretariat of Public Education (SEP).

Focus groups allowed to gather eighteen school directors and one assistant director in four stages. Besides, interaction among participants was used to obtain greater wealth of content starting with demographic data collected by an online questionnaire via Google Forms. This information shaped the sample with data related to position, management experience, age, educational levels covered by the institution, enrollment rate, number of collaborators, and student socioeconomic profile (Table 2). Selected participants for focus groups shared at least the common feature of being school directors in Mexico City and the Metropolitan Zone of the Valle de México.

It was decided to conduct four focus groups: the first of them had six participants; the second and third, four; and the fourth, five participants. All groups were conducted by one of the researchers, who acted as moderator, introduced the initial questions, directed the flow of the discussion, and mediated the emerging questions. The platform used to host the meetings was Google Meet, which allowed to record the sessions (with the participants permission) for subsequent transcription aided by GoTranscript. Approximate duration of each focus group session was 90 minutes.

Table 2. Participants’ profile in focus groups.

|

Focus group |

Director |

Key |

Current position |

Managerial experience |

Age |

Education levels at the institution |

Enrollment |

Number of collaborators |

Students’ socioeconomic status |

|

1 |

1 |

F1D1 |

General management |

6 |

29 |

Preschool |

40 |

13 |

Medium |

|

1 |

2 |

F1D2 |

Administrative management |

1 |

25 |

Preschool, primary, secondary |

740 |

75 |

C-, C, and C+ (medium) |

|

1 |

3 |

F1D3 |

TechnicalManagement |

9 |

63 |

Preschool, primary |

400 |

100 |

High |

|

1 |

4 |

F1D4 |

Preschool Management |

8 |

57 |

Preschool, primary, secondary, high school |

750 |

250 |

High |

|

1 |

5 |

F1D5 |

Academic and middle & high school Mgmt. |

29 |

50 |

K-12 |

690 |

180 |

Medium, medium-high |

|

1 |

6 |

F1D6 |

Preschool Management, Primary school coord. |

6 |

29 |

Preschool, primary |

290 |

34 |

Medium-low |

|

2 |

1 |

F2D1 |

Secondary school Management |

3 |

46 |

Preschool, primary, secondary, high school |

800 |

230 |

High |

|

2 |

2 |

F2D2 |

>Preschool Management |

20 |

52 |

K-12 |

400 |

120 |

A, B (high) |

|

2 |

3 |

F2D3 |

General Management |

15 |

57 |

Preschool, primary, secondary, high school |

3000 |

300 |

Medium |

|

2 |

4 |

F2D4 |

Sub-Directorate General |

3 |

28 |

Preschool, primary, secondary high school |

130 |

30 |

Medium-low, low (D) |

|

3 |

1 |

F3D1 |

General Management |

12 |

54 |

Preschool, primary, secondary, high school |

700 |

130 |

Medium |

|

3 |

2 |

F3D2 |

General Management |

6 |

44 |

Preschool, primary |

200 |

80 |

A, B (high) |

|

3 |

3 |

F3D3 |

High school Management |

10 |

54 |

Preschool, primary, secondary high school |

1200 |

300 |

Medium-high |

|

3 |

4 |

F3D4 |

General and Administrative Management |

6 |

28 |

Preschool, primary, secondary |

600 |

100 |

Medium |

|

4 |

1 |

F4D1 |

General Management |

15 |

49 |

Preschool, primary y secondary |

350 |

30 |

Medium |

|

4 |

2 |

F4D2 |

General Management |

35 |

53 |

Preschool, primary, secondary, high school |

600 |

120 |

Medium- alto, high |

|

4 |

3 |

F4D3 |

General Management |

8 |

40 |

Preschool, primary, secondary, high school |

830 |

200 |

Medium, high |

|

4 |

4 |

F4D4 |

General Management |

15 |

50 |

Preschool, primary, secondary |

600 |

150 |

Medium, high |

|

4 |

5 |

F4D5 |

General Management |

2 |

58 |

Preschool, primary, secondary, high school |

460 |

100 |

Medium, mediumhigh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Authors (2023).

Information analysis

Selecting a qualitative approach facilitated a flexible analysis which fluctuated between the manifestation of events through the participants’ discourse and the interpretation from the researchers’ iterative discussion to create both categories and subcategories. This allowed to reconstruct the speakers’ reality around their lived experiences as managers of educational institutions during the contingency.

The reconstruction had a holistic approach based on the ladder of inference an inductive tool proposed by Argyris (1999, p. 86): [This model explain how individuals understand the world]. Thus, as first step there was the identification of information from a first reading of each of the focus groups transcriptions, to identify the units of meaning. Moving forward to the second step, the meaning of those units was jointly discussed, which allowed to group them into different categories to ascend to the third level of analysis, to interpret what participants expressed. Some of the categories were then subdivided and finally compared to the findings in the literature.

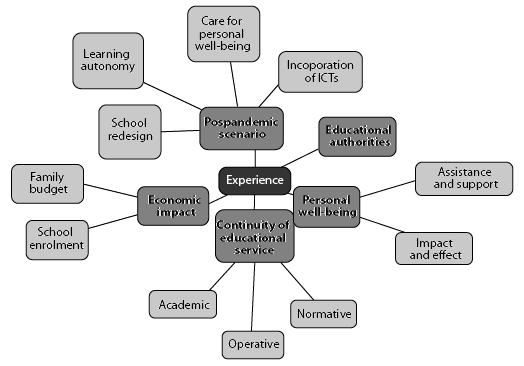

In order to comply with scientific rigor, the research used peer review criteria and saturation in the analysis and credibility in the findings: peer review, a constant during the whole process of analysis, and saturation based on conditions in relation to the emerging and developed categories in terms of their dimensions and the relationships established between them. The management of information obtained in each analysis stage was joint and agreed between researchers until they accomplished the construction of the categories shown in Figure 4.

Credibility of the findings was achieved through the acknowledgment of information on the part of individuals collaborating in this study, as they were the ones who lived these experiences.

The findings derived from the information analysis are shown below. With a focus on identifying the units of meaning and guarantee participants’ confidentiality, the following nomenclature was applied: F for focus groups and D for each manager or director. Thus, F1D1, for example, refers to one of the managers belonging to the first focus group.

Results and discussion

To provide answer to the research question —What was the managerial experience in the educational institutions in order to face the crisis derived from the closure of school centers during the pandemic?— the information gathered from school directors in the different focus groups was analyzed. The categories and subcategories emerged from here are indicated in Figure 4. To illustrate each of them, the most significant units of meaning were selected. This analysis identified the diversity of responses that school directors provided about the organizational model designating the institutional decision and actions, as stated by Martín-Moreno (2007a). To present these findings in a graphic form, CmapTools was used to elaborate the semantic map.

Source: Authors (2023).

Economic impact

As pointed by CEPAL (2020), negative effects on education were visible. A first finding is the economic impact on different spheres caused by the la pandemic. For example, variations in the family income impacted enrollments with contrasting effects: those families who could not pay school prices changed to other school with lower fees, other tried to enroll their children in public schools, and other opted not continue schooling, something which mainly affected preschool levels.

Several preschool groups must be suspended, mostly the ones having the youngest children. First and second year of kindergarten had a considerable enrollment drop. (F2D1)

As enrollment decreased, school incomes were not the expected, which impacted the retribution of school staff and payment to suppliers, something that was particularly critical for institutions or educational levels committed to established contracts. Contrarily, some institutions or even educational levels within the same institution emerged strengthened in terms of income and could face the economic impact in a different way.

Kindergarten was the hardest hit area. From 100 enrollments per year we went down to 35, what implied lots of dismissals. (F4D4)

A second finding associated to the enrollments shows a contrasting situation: those institutions showing a decrease in the number of students when tuition fees could no longer be afforded, and those institutions who became recipient of those changing to lower fee schools and had an increase of students.

I was really hard, being a small school, as we were still in investment phase and at closure, kindergarten enrollments were reduced to a 60 %. (F1D1)

Obviously, the COVID affects us in many ways, as it does to all, but despite everything we had an increase of enrollment by 7 % in total, new enrollments by 12 %…, even though we are an institution aimed to a medium, medium-low socioeconomic status. (F1D2)

Another finding related to this question is the support that institutions could provide regarding tuition fee costs.

With respect to tuition fees, we offered discounts. The tuition fee remained unchanged from one year to the next, and we maintained the discount offered. (F1D3)

This forced some schools to adjust their payroll models to the number of staff members or even dispense with external suppliers.

We have both staff and working time reduction as insolvency increased. It is necessary to create strategies not just to keep the boat afloat -having healthy finances is already hard-but also to make parents understand that service and ordinary expenses are still the same. (F2D3)

Continuity of educational service

Having the previous questions in mind, different strategies were developed in the academic, operative, and regulatory spheres. Within the academic field, all decisions aimed to coordinate the studies: curriculum and pedagogical activity, technological support, and teacher training. As observed by Castellanos et al. (2022), institutional support was crucial.

With respect to curriculum and pedagogical activity, they must adjust to new realities. This implied reorganizing the subject areas and the distribution of academic activities, even outside the traditional class schedule.

Obviously, it was essential to readjust schedules, but also to perform a curriculum prioritization, so that the aim was neither to teach it all, nor to teach it in the same way. (F4D2)

In this new context, technological support became crucial for all and involved different actions and investments according to the circumstances of each institution. While some schools had integrated technologies so far, others had to start from scratch.

With respect to technologies, we had worked with Google Suite, specifically Drive and Classroom, but not as intensively as it is used now. (F4D3)

My kindergarten was the less technological place in the world. My children run, played, flew kites… and this turned against me because I realized we were a galaxy away of facing the situation that was coming. (F2D2)

Likewise, a series of decisions needed to be addressed regarding teachers’ skills in different stages: the first of them when schools tried to provide an immediate response to the needs and secondly, when the institution planned the training.

We spent like three days before starting our online classes in a regular way. The high school faculty trained the rest of professionals: preschool teachers, primary, secondary, et cetera. (F3D1)

And, as summer arrived, the training in Google Suite apps was intensive for all the teachers, so they could master their management. (F4D3)

To accomplish this operation different support services and resources were generated. For example, loans of equipment and furniture, and the possibility of developing audiovisual material from the institution.

And we also identified which teachers may lack connectivity, equipment, resources for special needs, so we can provide them. If they do not have their own equipment, the school provided one to all those who required them. Or if the equipment was not good enough, of a good speed to go online with their teachers, they were offered financial support to improve the service at home. (F3D2)

They were offered the possibility for the teachers to go to the school, record their classes there, but having all the equipment within the room. (F1D4)

For example, we even went to our students’ houses and bring them their kindergarten benches and notebook simples, and putting in everything a lot of care, but we have dared to do things, to think and act. (F4D2)

Finally, the regulatory includes the guidelines to work and teach online, the school educational program, and the monitoring of governmental plans to ensure the return to normal activities when possible.

To accomplish this, some strategies were followed in three stages. The first of them established the guidelines to work and teach online, including dress code, the way to perform in front of the camera, and the use of technological too, among others.

And the tenured teacher, besides the blackboard stands before the camera (we use a Tablet in fact) and speaks as in a lecture. (F2D4)

A second line of action was to ensure the educational program, which included regulatory adjustments. The former implied the question of academic integrity in the evaluation of learnings, as well as subjects on digital citizenship.

It was a huge leap, to adapt our policies to explain out there that there is a digital citizenship and that you make an impact, not just the habitual copy-paste. In fact, if you are in the virtual classroom, you are a citizen in that environment, and as such you must comply with certain behaviors and follow certain rules, so everything works fine. (F1D2)

The third strategy provide continuity to all that was established by the governmental authorities when the return to in-class activity was possible, what implied that schools must develop their strategies regarding health protocols.

What we did was to hire an international company to define all the regulations on returning to class. We conducted a whole blended-learning logistics and established the security protocols the staff needed for the students and on their attendance to school. (F1D4)

Personal well-being

As in other reported experiences (López et al., 2021), institution directors participating in this research showed their concern for meeting the required levels of personal well-being for teachers, the work equipment, and the needs of students and guarantors with different actions such as a discussion groups, community support, class flexibility, and constant, close communication.

We had discussion groups, talked to the psychologists, external staff, just to bring in a bit of emotional support, where possible. (F3D3)

We have tried to offer support to the female teachers and the stressed staff through personal coaching, and in the general training one of the sessions is addressed to emotional work and management. (F4D3)

This emotional part with the work team has been basically support and trust. How to listen to them, stop so they can reflect and bring in some faith (or a lot), cultivate empathy with them and show them not to expect so much of themselves as now it is time to watch over ourselves, the children, leave aside plans and programs when necessary, and just listen. Sometimes children, young people feel the need to talk because they are living their own reality and some of them have note even left their home. (F4D1)

At least parents appreciate the effort the school makes to prevail, and this gives them peace of mind. Because there is a routine: classes begin at certain hour, fishing at another, there is a teacher, an evaluation, an assigned tutor helping their children, someone who answers the phone, someone who replies to the emails, so they do not feel lost. (F3D3)

Similarly, personal well-being was impacted by excessive workload, what blurred work schedules and times, and personal and family life.

The first thing I got was work, work, work. That is, no spring break but more work, planning, and building groups of design thinking. (F4D2)

On the other side, I think teachers have worked like 800 times more than the usual, they are permanently online. Even more, we have to ask them not to reply to emails around the clock. (F3D1)

There is a lot of concern though. Psychosis even. Stress caused by work overload and panic derived from all these questions. However, I think every cloud has a silver lining, and in this case are the learnings about this pandemic scenario. (F2D3)

Educational authorities

Educational authorities also faced adaptation challenges in relation to management of uncertainty (Caputo & Pérez, 2021). In this sense, it must be highlighted that during all the process here described, institutions felt the lack of clarity with respect to the directions to follow, support, or even of the presence of the educational authorities.

Supervisors of the different sections also act in accordance to, well, their own criteria; sometimes even there is disagreement between them. But the truth is that it was not common. (F4D1)

Basically, everything the same… This is the way with the SEP. At first, uncertainty, things were nuclear. They ask for things they do not want, virtually they ask for proves, so you sent them pics of pics, there is nothing more to be done. They ask for things they do not even do themselves. (F4D5)

Zero support. If we live in uncertainty, they do not even know what is going on. When we were finishing the previous year, we wanted to know how everything was going, there was a point in which we decided: “Let’s forget about this, do not pay attention to them, let’s foresee ourselves the possible scenarios”. (F4D3)

My education authority was missing, zero, nonexistent. I have both technical secondary school and tech baccalaureate; it is not the same, but a smaller field. But literally they left us on our own and told us: “Scratch your own backs, do what you need”, meaning what we could. (F2D4)

Post-pandemic scenario

The post-pandemic scenario poses different challenges for school directors. Some of them are the integration of technology to the educational model and curriculum, meeting the personal well-being requirements for emotional health, prevent and cure illness, fostering autonomy in the academic work of teacher and students, and redesigning a new school where change and uncertainty are part of the educational reality.

We have learned a lot from hybrid systems. Now we need to rely more on technology, use much more the apps, continue prioritizing the curriculum instead of teaching it all, maintain hygienic measures and health promotion, and socio-emotional routines; do routines conducted by group teachers with long-term continuity, and put the individual above the program. (F4D2)

Autonomy and constant learning. It seems to me that this has been a great opportunity for both teachers and students and being self-taught. (F4D1)

We were bound to envision a new school. All of us in the educational sphere now will be future pedagogues and everything we do, write, document, and think today will be part of the schools of the future. (F3D3)

In all, as indicated by Kochen (2020), it is a question of forgetting the learnings and return to old practices.

Conclusions

The impact of the pandemic affected unevenly to educational institutions. Those of private funding in Mexico, the focus of this research, evolved different according to their circumstances, in terms of the educational model used as guideline, infrastructure, size, coverage, teachers’ qualifications, openness to innovation, and financial shape.

In all, the strategies —understood as the measures and actions adopted by the management to face the crisis— were of different nature. While some of them focused on financial support, other put their efforts in the teaching community well-being.

Although the pandemic situation implied an unknown scenario for all the educational centers, from a comparative perspective, those institutions of versatile organization and with ICT incorporated to their educational model had better conditions that facilitated their adaptation to the new remote learning ecosystem, and even they came out stronger.

The experiences shared by the managers interviewed in focus groups showed that their vision when managing the crisis scenario and their ability to adapt to change were crucial for the continuity of the educational service. In this sense, gathering the managerial experience in the context of the pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus is a contribution to the field of educational institutions managements in complex environments and times of crisis.

Looking ahead, further studies should be conducted to understand the managerial experience on the challenges posed by times of crisis for public institutions, as one of the limitations of this study is that it only refers to the experience of managers of private institutions. Widening the scope will make possible to analyze this phenomenon through a larger sample and comparative studies in the target population.

Post-pandemic future, still uncertain, has accelerated the changes already present in the literature (Ortega, 2008; Hernando, 2016) and put traditional institutions on alert, as they will have to open themselves to innovation in order to survive, rethinking their educational models, and letting aside ad-lib managerial practices. The pandemic was a turning point, and schools cannot follow their older ways. Undoubtedly the role of school directors is complex due to their myriad functions accomplished between policies and reality (Kochen, 2020).

References

Argyris, C. (1999). Conocimiento para la acción: Una guía para superar los obstáculos del cambio en la organización. Granica. https://bit.ly/3kZrb1l

Barbour, R. (2018). Doing Focus Groups. Sage. https://bit. ly/3Jkul9g

Bautista, A., Cerna, D., & Romero, R. (2020). Representación social de la educación a distancia en época de COVID-19, en estudiantes universitarios. Miradas, 15(1), 24-34. https://doi.org/10.22517/25393812.24468

Caputo, S., & Pérez, J. (2021). Liderazgo y educación: Reflexiones en tiempos de pandemia. Diálogos Pedagógicos, 19(38), 73-94. https://bit.ly/3JmxTbp

Cárdenas, D., Hernández, N., & García, J. (2022). Transformaciones de la práctica pedagógica durante la pandemia por COVID-19: Percepciones de directivos y docentes en formación en educación infantil. Formación Universitaria, 15(2), 21-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/ S0718-50062022000200021

Castellanos, L., Portillo, S., Reynoso, O., & Gavotto, O. (2022). La continuidad educativa en México en tiempos de pandemia: Principales desafíos y aprendizajes de docentes y padres de familia. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 21(45), 30-50. https://dx.doi. org/10.21703/0718-5162.v21.n45.2022.002

CEPAL (2020). América Latina y el Caribe ante la pandemia del COVID-19: Efectos económicos y sociales. Informe Especial COVID-19. 3 de abril. https://bit.ly/3YrMzKj

Collins, R. (2009). Cadenas de rituales de interacción. Anthropos. https://bit.ly/3kZtzoP

Cortés, J. (2021). El estrés docente en tiempos de pandemia. Revista Dilemas Contemporáneos, 8. https://doi. org/10.46377/dilemas.v8i.2560

Daniel, M., Breuer, J., & Mayer, H. (2013). Focus Groups: Eine besondere Art Gruppen zu interviewen. ProCare, 18, 20-23. https://bit.ly/3JmMVxQ

De Vicenzi, A. (2020). Del aula presencial al aula virtual universitaria en contexto de la pandemia de COVID-19. Universidad Abierta Interamericana. https://bit.ly/41WlK4e

Dos Santos, B., Ribeiro, S., Scorsolini, F., & Dalri, R. (2020). Ser docente en el contexto de la pandemia de COVID-19: Reflexiones sobre la salud mental. Index de Enfermería, 29(3), 137-141. https://bit.ly/3LUXdXG

Fuentes, O. (2015). La organización escolar: Fundamentos e importancia para la dirección en la educación. Varona, 61, 1-12. https://bit.ly/3yk0ojx

Fullan, M. (2016). La dirección escolar: Tres claves para maximizar su impacto. Morata. https://bit.ly/3Zyznor

Gajardo, K., Paz, E., Salas, G., & Alaluf, L. (2020). El desafío de ser profesor universitario en tiempos de la COVID-19 en contextos de desigualdad. Educare, 24, 1-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.15359/ree.24-s.14

García Aretio, L. (2021). COVID-19 y educación a distancia digital: Preconfinamiento, confinamiento y posconfinamiento. RIED. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 24(1), 9-32. https://doi.org/10.5944/ ried.24.1.28080

González Calvo, G., Barba, R., Bores, D., & Gallego, V. (2020). Aprender a ser docente sin estar en las aulas: La COVID-19 como amenaza al desarrollo profesional del futuro profesorado. International and Multidisciplinary Journal in Social Sciences, 9(2), 46-71. https://doi. org/10.17583/rimcis.2020.5783

González Fernández, R., Khampirat, B., López, E., & Silfa, H. (2020). La evidencia del liderazgo pedagógico de directores, jefes de estudios y profesorado desde la perspectiva de las partes interesadas. Estudios sobre Educación, 39, 207-228. http://doi.org/10.15581/004.39.207-228

González Jaimes, N., Tejeda, A., Espinosa, C., & Ontiveros, Z. (2020). Impacto psicológico en estudiantes universitarios mexicanos por confinamiento durante la pandemia por COVID-19 [inédito]. https://doi. org/10.1590/SciELOPreprints.756

Guerrero, L., Pérez, M., Dajer, R., Villalobos, M., & Barrales, A. (2020). La Facultad de Pedagogía y sus estrategias ante la emergencia sanitaria por el COVID-19. Emerging Trendes in Education, 3(5). https://bit.ly/3yhwFrB

Hernández, A. (2020). COVID-19: El efecto en la gestión educativa. Revista Latinoamericana de Investigación Social, 3(1), 37-41. https://bit.ly/3Ys03WC

Hernando, A. (2016). Viaje a la escuela del siglo XXI: Así trabajan los colegios más innovadores. Fundación Telefónica. https://bit.ly/3moXjfc

Herrera, G., Salazar, L., Obando, M., & Vargas, C. (2020). Armonía en tiempos de ruido. Educare, 24, 1-3. https:// doi.org/10.15359/ree.24-S.8

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (2021). Encuesta para la Medición del Impacto COVID-19 en la Educación (ECOVID-ED) 2020: Nota técnica. INEGI. https://bit.ly/3EZjKhF

Keleş, H., Atay, D., & Karanfil, F. (2020). Covid 19 pandemi sürecinde okul müdürlerinin öğretim liderliği davranişlari. Milli Eğitim Dergisi, 49(1), 155-174. https:// doi.org/10.37669/milliegitim.787255

Kochen, G. (2020). La gestión directiva o el liderazgo educativo en tiempos de pandemia. Innovaciones Educativas, 22(33), 9-14. https://doi.org/10.22458/ie.v22i33.3349

Krueger, R. (2002). Designing and Conducting Focus Group Interviews. University of Minnesota. https://bit.ly/2OdRYBm

López, V., Álvarez, J., Calisto, A., Aguilar, G., Barrios, P., Cárdenas, M., Briceño, D., Vera, M., Marinao, H., Romero, B., & Leiva, M. (2021). Apoyo al bienestar socioemocional en contexto de pandemia por COVID-19: Sistematización de una experiencia basada en el enfoque de Escuela Total. Revista F@ro, 1(33), 17-44. https://bit.

Martín-Moreno, Q. (2004). La dirección escolar y la conexión con el entorno. Enseñanza. Anuario Interuniversitario de Didáctica, 22, 103-138. https://bit.ly/3TJBmUG

Martín-Moreno, Q. (2007a). Desafíos persistentes y emergentes para las organizaciones educativas. Bordón, 59 (2-3), 417-429. https://bit.ly/3YpNMSt

Martín-Moreno, Q. (2007b). Organización y dirección de centros educativos innovadores: El centro educativo versátil. McGraw-Hill. https://bit.ly/3ZISbRC

Martínez, P. (2020). Aproximación a las implicaciones sociales de la pandemia del COVID-19 en niñas, niños y adolescentes: El caso de México. Sociedad e Infancias, 4, 255-258. https://doi.org/10.5209/soci.69541

Meza, M., Ortega, C., & Cobela, F. (2022). Tendencias investigativas sobre liderazgo y dirección escolar: Revisión sistemática de la producción científica. Revista Fuentes, 24(2), 234-247. https://doi.org/10.12795/re

Mieles, M., Tonon, G., & Alvarado, S. (2012). Investigación cualitativa: El análisis temático para el tratamiento de la información desde el enfoque de la fenomenología social. Universitas Humanística, 74, 195-225. https://bit. ly/3F3VVp1

Morgan, D. (1997). Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. Sage. https://bit.ly/3Jl5Vwv

Ortega, F. (2008). Tendencias en la gestión de centros educativos. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos (México), 38(1-2), 61-79. https://bit.ly/3ZrZKfN

Pachay, M., & Rodríguez, M. (2021). La deserción escolar: Una perspectiva compleja en tiempos de pandemia. Polo del Conocimiento, 6(1), 130-155. https://bit.ly/3LT0bfe

Pérez, E., Vázquez, A., & Cambero, S. (2021). Educación a distancia en tiempos de COVID-19: Análisis desde la perspectiva de los estudiantes universitarios. RIED. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 24(1), 331-350. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.24.1.27855

Picón, G., González, K., & Paredes, N. (2020). Desempeño y formación docente en competencias digitales en clases no presenciales durante la pandemia COVID-19 [inédito]. https://doi.org/10.1590/SciELOPreprints.778

Ramírez, R., Gutiérrez, J., & Rodríguez, M. (2020). Orientaciones para apoyar el estudio en casa de niñas, niños y adolescentes: Educación preescolar, primaria y secundaria. Secretaría de Educación Pública. https://bit.ly/3yklCxS

Ruiz, G. (2020). COVID-19: Pensar la educación en un escenario inédito. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 25(85), 229-237. https://bit.ly/3zeUCjr

Sandoval, C. (2020). La educación en tiempo del COVID-19. Herramientas TIC: El nuevo rol docente en el fortalecimiento del proceso enseñanza-aprendizaje de las prácticas educativas innovadoras. Revista Tecnológica-Educativa Docentes 2.0, 9(2), 24-31. https://doi. org/10.37843/rted.v9i2.138

SEP (2023). Sistema Interactivo de Consulta de Estadística Educativa. Secretaría de Educación Pública. Accedido 7 de marzo. https://bit.ly/2F2s29h

Valdivia, P., & Noguera, I. (2022). La docencia en pandemia, estrategias y adaptaciones en la educación superior: Una aproximación a las pedagogías flexibles. Edutec. Revista Electrónica de Tecnología Educativa, 79, 114-133. https://doi.org/10.21556/edutec.2022.79.2373

Vega, G., Ávila, J., Vega, A., Camacho, N., Becerril, A., & Leo, G. (2014). Paradigmas en la investigación: Enfoque cuantitativo y cualitativo. European Scientific Journal, 10(15), 523-528. https://bit.ly/3JmH6Av

Conflict of interest declaration

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contribution to authorship declaration

Claudia Fabiola Ortega Barba participated in the processes of research, methodology, analysis, and conclusions as well as in the writing of the original draft, its review and edition.

Mónica del Carmen Meza Mejía contributed with the research, conceptualization, analysis and conclusions, as well as in the writing of the original draft, its review and edition.

José Francisco Cobela Vargas participated in the research, focus groups, analysis and conclusions, as well as in the writing of the original draft, its review and edition.

Ortega-Barba, Meza-Mejía, & Cobela-Vargas. (2023). Educating in Exceptional Times: Educational Institutions Management in the Post-Pandemic Era, a Qualitative Study in Mexico Schools. Revista Andina de Educación 6(2), 000623. Released under license CC BY-NC 4.0