Revista Andina de Educación 6(1) (2022) 006112

The relationship of home and instructional environments to L2 literacy development

Contexto escolar y familiar y su relación con el desarrollo de la alfabetización en una segunda lengua

Sara Isabel Rendón-Romeroa

, Macarena Navarro-Pabloa

, Macarena Navarro-Pabloa

, Eduardo García-Jiménezb

, Eduardo García-Jiménezb

a Universidad de Sevilla. Departamento de Didáctica de la Lengua y la Literatura y Filologías Integradas. C/Pirotecnia, s/n. 41013. Sevilla. España.

b Universidad de Sevilla. Departamento de Métodos de Investigación y Diagnóstico en Educación. C/Pirotecnia, s/n. 41013. Sevilla. España.

Received October 06, 2022. Accepted January 26, 2023. Published April 1, 2023.

© 2023 Rendón-Romero, Navarro-Pablo, & García-Jiménez. CC BY-NC 4.0

https://doi.org/10.32719/26312816.2022.6.1.12

Abstract

Home and instructional learning environments can influence children’s literacy development in English as a Foreign Language. The main objectives of this research are 1) to determine the influence of school and home elements on children’s literacy process and 2) to identify reading practices and English tasks carried out at home. The research counted with the participation of 142 pupils and their families belonging to two different bilingual schools from Seville, Spain. This study followed an ex post facto design with natural groups in which quantitative data were collected through questionnaires to families and qualitative data through observations of pupils. Data were analysed through the Mann-Whitney U test and discriminant analysis. Results show that the frequency of reading in front of children, the mothers’ help with English tasks at home, and a certain amount of extramural English influenced the literacy process. Furthermore, the study identified significant differences between the two schools in relation to literacy practices at home and parental involvement in schoolwork. The results obtained present relevant implications in promoting family training and involvement and engaging in interactive collaborations with the school.

Keywords: home environment, instructional environment, English as a Foreign Language, literacy, extramural English

Resumen

Los contextos escolares y familiares de aprendizaje pueden influir en el desarrollo de la alfabetización en inglés como lengua extranjera. El objetivo de esta investigación es determinar la influencia de los elementos de la escuela y del hogar en el proceso de alfabetización e identificar las prácticas lectoras y las tareas realizadas en casa. La investigación contó con 142 discentes y sus familias pertenecientes a dos colegios bilingües de Sevilla, España. Este estudio siguió un diseño ex post facto con grupos naturales en el que se recogieron datos cuantitativos a través de cuestionarios y datos cualitativos a través de observaciones. Los datos se analizaron mediante la prueba U de Mann-Whitney y un análisis discriminante. Los resultados muestran que la frecuencia de lectura, la ayuda de las madres en las tareas de inglés en casa y un inglés extramural determinado influían en el proceso de alfabetización bilingüe. También se identificaron diferencias significativas entre los dos colegios en relación a las prácticas de alfabetización en casa y la ayuda e implicación de la familia en las tareas escolares. Los resultados obtenidos presentan implicaciones relevantes a la hora de promover la formación e implicación de las familias, y su colaboración con la escuela.

Palabras clave: contexto familiar, contexto escolar, Inglés como Lengua Extranjera, alfabetización, Inglés extramural

1. Introduction

The present research focuses on literacy in two languages. Bauer & Colomer (2017) mentions that ‘biliteracy’ refers to what ‘students are able to do with print across their languages’ (p. 1). The author also highlights a sociocultural aspect for the term: ‘biliteracy is viewed as a skill that develops outside the classroom, which emergent bilinguals bring with them when they enter the school’ (p. 7). This may be related to the idea that contextual elements, as family reading practices, are relevant during the literacy development of children. Thus, the two environments of classroom and home are relevant for this study.

Classroom environment is crucial for successful second language acquisition ‘as a social context for speaking and listening’ (Datta, 2007, p. 23). Many studies show that classroom areas (Neuman & Roskos, 2002; Jolliffe & Waugh, 2015), natural and real situations (Beecher & Makin, 2002), and the kind of activities or resources used (Browne, 2001) directly influence a child’s achievement of a proper English reading level. Moreover, it is important to mention that the literacy process starts when children are born and it is influenced by the sociocultural context which surrounds them (Neuman & Roskos, 2002). The immediate context which surrounds children is home. The activities carried out in this context can significantly correlate with higher achievement in school literacy (Alston-Abel & Berninger, 2018). In this line, it is necessary to mention that the relationship between children and adults seems to be crucial for the development of languages. As Vygotsky (1978) argues, children learn from their environment. Adults and peers serve as a guidance for problem-solving and learning collaboration (Zone of Proximal Development). Thus, the relationship between parents and children is crucial, as well as their participation in daily reading activities at home.

For these reasons, this study tries to answer the following questions: Do instructional and home learning environments influence children’s literacy development in the same way? What can each context do to help children acquire a proper development? Is extramural English relevant in order to acquire a higher achievement at school?

The influence of learning environments on children’s literacy process in English

Linguistic factors, individual characteristics and methods of teaching reading are not the only aspects which may influence a children’s foreign language literacy process. The social, physical, psychological and pedagogical contexts in which the literacy process in a foreign language occurs can affect children’s achievement and attitudes (Kokko & Hirsto, 2020). These contexts, usually classrooms and homes, become learning environments which can influence children depending on how physical spaces are organized and what literacy activities are developed., teachers and parents) collaborate to improve a child’s literacy development. Consequently, physical and social relations are important factors for the learning environments (Kokko & Hirsto, 2020). Home environment as a learning space should also be examined in relation to children’s development (Puglisi et al, 2017; Kokko & Hirsto, 2020).

The instructional context and the home contexts are learning environments which are crucial for successful foreign language acquisition. These two environments could as well be called inside and outside instructional environments, the latter also called “language learning beyond the classroom” (LBC) (Reinders & Benson, 2017), which refers to any learning that occurs outside school. Educators describe this concept as: “out-of-class, after-class, extra-curricular, self-access, out-of-school, or distance learning” (Reinders & Benson, 2017). Lancaster (2018) refers to it as “extramural exposure”. In this paper, all definitions being considered, the researchers decided to use the term “Extramural English”, as it seems to be more comprehensive to refer to any activity performed in English out of school. This is a term introduced in 2009 by Sundqvist referring to any English input received “outside the walls of the English classroom” (p. 6). Sundqvist provides some examples of Extramural English such as watching films, TV series, music videos, listening to music, reading books, reading newspapers, searching on the Internet, or using social networks.

Regarding activities inside the instructional environment, interaction and situations based on real experiences play an essential role.Interactions should be created in natural contexts or through activities created inside the classroom which can enable children to enhance meaning. In addition, pupils learn and develop literacy when they work in collaboration or with peers. Children learning their first and second languages need many opportunities to be able to interact using the languages in shared contexts. They learn by relating languages to people and contexts (Freinet, 1974; Beecher & Makin, 2002; Neuman & Roskos, 2002; Montessori, 2006; Datta, 2007). So, they interiorize which language they need to use with one specific person or in a specific context. For example, they can talk English with their teacher at school but Spanish with their mother at home.

In order to facilitate interaction and learning inside the classroom, Neuman & Roskos (2002) mention that this space should be “large” and “clear”. For this reason, the creation of different areas in the classroom, such as corners, small libraries and some places for games or silent reading, all create opportunities for children to work individually or in groups for a better development of their literacy (Browne, 2001; Datta, 2007; Jolliffe & Waugh, 2015). A positive atmosphere and interactions inside the classroom could also be carried out if useful and motivating activities and resources are properly employed.

Regarding activities, Browne (2001) states that “early literacy activities should provide children with the opportunity to extend what they already know by enabling them to explore, experiment, take risks and reflect in ways that are immediately connected to print, books and stories” (p. 51). Neuman & Roskos (2002) mention that “appropriateness, authenticity and utility” should be characteristics of the materials used in order to help connect children’s understanding. Thus, proper materials may be related to children’s needs and interests by promoting the use of real texts and situations which they can encounter and can allow them to understand the real application of the language. Consequently, if teachers provide proper resources, children would give more real sense to reading activities (Browne, 2001). Fons (2002) also mentions that resources in the instructional environment should be appropriate in order to create interaction opportunities that mimic a child’s daily life.

Furthermore, another important aspect of the literacy process promotes the interactions between multiple learning environments. Children need to create connections between home and school through common contexts as crucial factors to improve literacy development (Neuman & Roskos, 2002). The collaboration between the teachers and parents of these different environments is important so that pupils’ own sociocultural contexts could be connected to the classroom’s reality. School and home are learning environments which become very important in their foreign literacy process as they directly influence children’s early language development. According to Reinders & Benson (2017, p.: 11), teachers should be able to “link classroom teaching to their students’ LBC activities” and suggest doing project work in order to bring these LBC contexts to the class. If teachers and parents collaborate in the teaching-learning process, pupils will have a better language learning development. This collaboration would also be beneficial in order to improve communication, carry out daily reading and writing practices in two languages and create activities based on real experiences (Beecher & Makin, 2002; Wright & Peltier, 2016; Theodotou, 2017).

Parents “can provide opportunities for learning, recognition of the child’s achievement, interaction around literacy activities, and a model of literacy” for developing readers and writers (Hannon, 1995, p. 51). However, parents need to understand how the literacy process can also be carried out at home as a link to English literacy practices in the classroom. Thus, parents and teachers’ collaboration should focus on the development of programs which help parents achieve objectives in terms of reading interactions (Kern et al., 2018). Furthermore, introducing content in the classroom about what parents usually do at home is feasible and can improve the development of literacy skills. Parents may create materials which children could take to classrooms and which are not usual to find inside them (Caesar & Nelson, 2014).

Moreover, extramural English is considered to be important for a proper development of children’s literacy in the foreign language. For this reason, materials available at home, the literacy opportunities in their neighbourhood, parental encouragement and expectations for literacy, their contact with school, the library visits, the literacy environment at home and early reading to children, parents’ educational level and their income are considered to be important factors influencing the literacy development of young children (Hannon, 1995). Consequently, parental involvement and education seem also to be important in this early development.

This literacy environment, according to Carroll, Holliman, Weir & Baroody (2019), could also be related to the socioeconomic status of the families. More specifically, family literacy practices, the frequency with which parents read to children and the number of books available at home seem to be important reading predictors (Harris, Loyo, Holahan, Suzuki & Gottlieb, 2007). Besides, the mothers’ literacy level also contributes in this literacy development (Puglisi et al., 2017). The literacy environment is directly related to the frequency that children have a look at books at home (Wiescholek, Hilkenmeier, Greiner & Buhl, 2018). Thus, home literacy activities can significantly correlate with higher achievement in school literacy (Alston-Abel & Berninger, 2018; Wood, Fitton & Rodríguez, 2018) and, as Hannon (1995) states, —the key is to involve parents more in the teaching of literacy— (p. 1). So, in order to provide proper early language acquisition, families should be a model to follow, a positive attitude towards reading should be encouraged, parents should read to children every day, families should collaborate with schools, and they should have adequate books related to children’s needs and interests (González Álvarez, 2003). Thus, all these aspects will be taken into account in the analysis of this research since this paper tries to present data related to how instructional and home environments can influence the English literacy process of Spanish children.

Methodology and materials

The present paper is part of a wider research carried out from 2016 to 2019, whose main aim was to determine the effectiveness of a phonics method in the biliteracy process of Spanish children from two different schools in Seville, Spain, School 1 (public centre) and School 2 (private centre) both implemented a new program called Jolly Phonics with small groups of preschool students. This method was chosen due to the good results in developing good English reading in children from the United Kingdom. Because the program had achieved strong reading results with children in the United Kingdom, this study tried to analyse the method´s effectiveness for Spanish children. Thus, it was possible to collect data during the whole school year (2017-2018) with the use of different activities to compare the results with those of English kids to determine what reading age in English Spanish children could reach. Finally, the results of this study pointed out that the phonics method helped to develop children’s level of English literacy skills. Although pupils from both schools reached the same English reading age, (almost 6 years old (Table 1), after performing a final reading test, pupils from School 2 seemed to achieve a more advanced level of development (Author, 2019), since results in this study pointed out that pupils from School 2 seemed to be in a lexical route (Cuetos, 2008), as children could decode in a more automatized way and read any word or nonword and understand the meaning of common words. So, they were acquiring a more comprehensive way of reading.

Table 1. Comparison of the actual age and the Age Reference Scale of Jolly Phonics in both schools.

|

Actual Age |

English |

Sign |

|

|

Treatment Groups A, B, C, D (School 2) |

7.1 |

Group A: 5.6 Group B: 5.6 Group C: 5.9 Group D: 5.5 |

0.001** |

|

Treatment Group A (School 1) |

7.1 |

Group A: 5.7 |

0.001** |

|

|

|

|

|

Note: **Statistically significant p< 0.01. Source: Rendón Romero (2019).

Considering the differences among schools, it seemed to be important to more profoundly analyze the aspects which could be influencing these differences. Thus, the main research question of the present paper is:

Do instructional and home environments influence the literacy process in English of Spanish children in the 1st year of Primary Education?

Objectives

The main objectives for this study are:

(1) To determine the instructional learning environment regarding English literacy practices.

(2) To determine the ideal home learning environment regarding English literacy practices.

(3) To identify the influence of extramural English on the literacy development of children.

(4) To compare the instructional and home learning environments as well as the extramural English regarding different types of schools.

Design

This study employed a quantitative non-experimental method to compare the pedagogical contexts defining the instructional and home learning environments. The research design used to answer this study’s objectives is an ex post facto design with natural groups (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2012). The contrasted groups were naturally created and independent variables were not manipulated. Additionally, a correlational study allowed us to show the main traits defining the instructional learning environments.

Sample

The study selected contrasting school centres from state and private schools. School 1 is a bilingual state primary school which receives students from families with average socioeconomic status. In the first year of Primary Education (6-7 year old Spanish children), 52 pupils participated in the study, divided into two groups (1A and 1B). In addition, parents also participated. School 2 is a bilingual private school which receives students from families with high socioeconomic status. In this case, four groups (A, B, C and D) from the first year of Primary Education (6-7 year old children) participated in the study. The overall number of pupils and families participating in this school was 89.

Each school headteacher signed an agreement at the beginning of the research process. In the same way, teachers were also informed and signed a school consent in which they agreed to participate in the study. Due to the fact that all participating pupils were underage, the corresponding parents were also informed and voluntarily signed another informed consent to participate in the project.

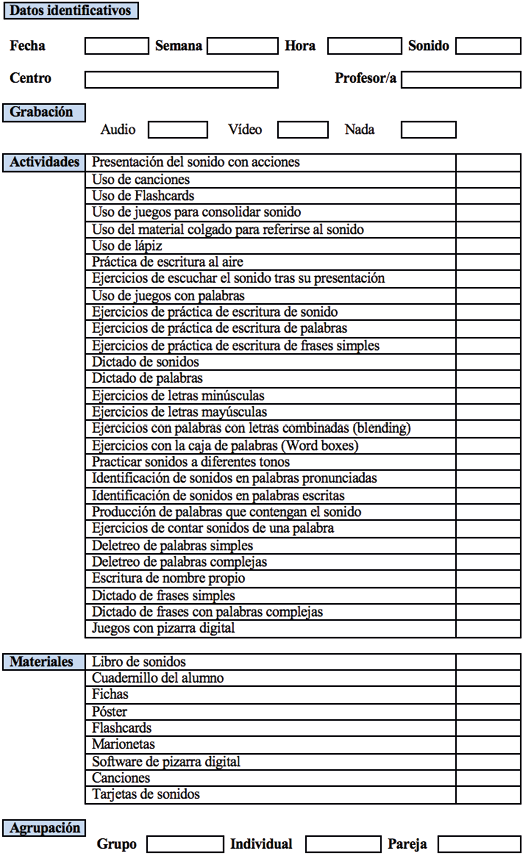

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected through daily participant observations in the classrooms at both schools. To do so, an observation template was created (Appendix A). The elements which were considered under observation were: instructional learning environment, the type of activities, materials and resources used, classroom areas, type of recording (audio, video, both) and type of grouping (individual, pairs, groups). In all observations, a video camera was used in order to record them or take photos and diaries were written down. During the whole year, students carried out different activities which were also registered and analysed. At the end of the year, the pupils took a final English reading test which could also provide important results. In order to analyse the continuous and final activities, a reduced sample (26 students from School 1 and 23 students from School 2) was selected since it was necessary to take just those students who completed all activities during the whole year and at the end so as to be able to compare the results throughout the whole year. Additionally, a discriminant analysis was carried out in order to compare the type of activities between both schools.

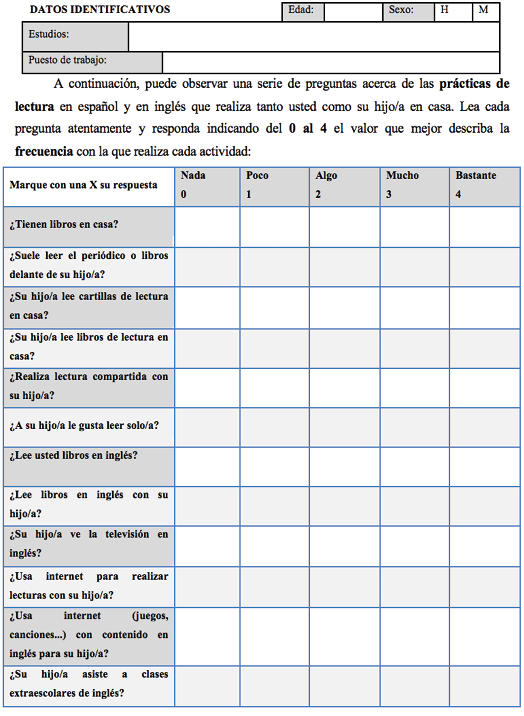

Regarding the home environment, a questionnaire was elaborated (Appendix B), based on a Likert scale. The main aim of this questionnaire was to discover the daily practices of reading in English performed at home at the beginning of the study. The questionnaire comprised 12 questions with values from 0 to 4. The reliability of the questionnaire was Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74. Items included questions related to the parents’ education, the frequency of parents’ reading at home, parents’ reading with and to children and the use of the Internet for practicing English.

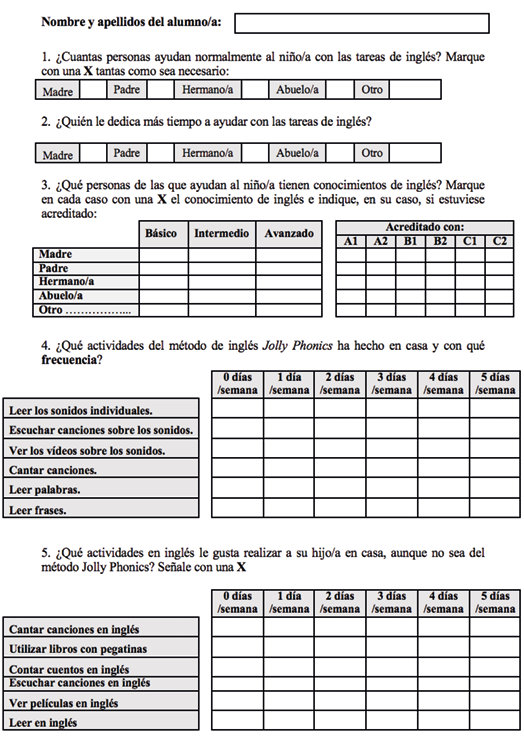

Furthermore, a second questionnaire (Appendix C) was also delivered to parents at the end of the study. This questionnaire was based on families’ support on the English tasks at home and the frequency of different activities performed at home. The reliability of the test was Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84.

The results obtained in the first questionnaire were analysed by using the Mann-Whitney U Test (due to the fact that the sample was lower than 30 in each school) in order to establish differences according to each school. The second questionnaire was also analysed through the Student’s T test [A1] since, in this case, the sample was higher than 30 in each school. The SPSS programme was used to carry out these two tests.

As it can be observed in the appendices, the instruments were elaborated in Spanish as it was the first language of the participating sample.

Results

The results presented in this paper show data regarding instructional and home environments to determine differences between pupils from both schools and to identify how these two learning environments can also influence pupils’ English literacy development.

Instructional learning environments

The classrooms in School 1 presented reading books in a small library and posters on the wall. Teachers placed desks so that all children could sit down to face the board (Figure 1). In some rare cases, this arrangement changed in order to place students in groups (Figure 2).

Source: Rendón Romero (2019).

Source: Rendón Romero (2019).

Teachers utilized the Jolly Phonics method through which children learn sounds first and then connect them to the letter shapes. As students make connections, they start identifying these letter-sounds in different word positions. Teachers projected book materials on the whiteboard in order to tell stories and work on vocabulary and comprehension questions. Additionally they reinforced the phonics methods with songs, flashcards, and worksheets for children to practice the content of each session.

Each session started with conversational questions followed by an engaging story used to introduce lesson content. Teachers followed the story by introducing comprehension and vocabulary activities in a whole group session although, sometimes, it could be performed individually. After students had finished, teachers reinforced vocabulary with songs and flashcard activities.. Students ended each session by individually completing a vocabulary worksheet. In the case of School 2, classrooms presented posters on the wall and a small library. Teachers placed desks in small groups so that children could sit down and work collectively. Finally, teachers used specific areas on the floor to practice reading skills (Figure 3).

Source: Rendón Romero (2019).

Source: Rendón Romero (2019).

While teachers utilized the same Jolly Phonics methods as that of School 1, they did not use pupils’ books in which pupils could look at the colourful pictures of the stories, read words or touch the shapes of the letters Instead teachers promoted student workbooks where different kinds of black-and-white exercises were presented so that pupils could practise reading and writing skills. They also used songs, flashcards and activities created by their own teachers.

Teachers emphasized whole group communicative activities with reinforcement through individual workbook exercises. Students ended most lessons by actively participating in group activities to summarize lesson content.

School 2 achieved a balance to perform group activities during half of the session complemented by individual student work.

Comparison between the instructional learning environments in School 1 and 2

Researchers used a descriptive analysis to understand the frequency with which each activity was used in each school (Table 2). School 1 became more systematic in the use of activities. This school importantly used the activity related to the identification of sounds in words (100%)with a high frequency of different activities. For example, this school worked on activities such as relating sounds to actions, songs, and flashcards. Students listened to sounds after introducing them, blending, word boxes, identifying sounds in written words and the use of books and worksheets (80-100%). In the case of School 2, the use of complimentary activities depended on the session. The activities mostly used were: relating sounds to actions, use of word boxes, identifying sounds in written words, production of words containing the sounds worked and the use of workbooks (60-80%).

The less frequent activities coincided in both schools in the case of dictations of sounds or words and the use of puppets (<40%). This may be due to the fact that the English phonics method is mainly focused on pre-reading skills and writing is a skill which appears less during the first year of Primary Education in English. Both schools also coincided in the use of games with words containing the sounds (40-60%) and production of words containing the sounds (60-80%) as they are activities which can be practiced so as to review sounds in a different way.

Table 2. Frequency of use of activities in each school (School 1 and School 2)

|

<40% |

40-60% |

60-80% |

80-100% |

100% |

|

|

Relating sounds to actions |

2 |

1 |

|||

|

Songs |

2 |

1 |

|||

|

Flashcards |

2 |

1 |

|||

|

Games to practice sounds |

2 |

1 |

|||

|

Use of the pencil |

2 |

1 |

|||

|

Listening to sounds after their introduction |

2 |

1 |

|||

|

Games with words containing the sounds |

1, 2 |

||||

|

Writing sounds or words |

1 |

2 |

|||

|

Dictation of sounds |

1, 2 |

||||

|

Dictation of words |

1, 2 |

||||

|

Blending |

2 |

1 |

|||

|

Word boxes |

2 |

1 |

|||

|

Identifying sounds in spoken words |

2 |

1 |

|||

|

Identifying sounds in written words |

2 |

1 |

|||

|

Production of words containing the sounds |

1, 2 |

||||

|

Counting the number of sounds in words |

2 |

1 |

|||

|

Sounding out words |

|

2 |

1 |

||

|

Use of the pupils’ book |

2 |

|

1 |

||

|

Use of worksheets |

2 |

|

1 |

||

|

Use of pupils’ workbooks |

1 |

2 |

|||

|

Use of puppets |

1, 2 |

||||

|

Individual and group activities |

2 |

1 | |||

|

|

|

|

Source: Authors (2023).

Note: 1=School 1; 2=School 2.

The discriminant analysis shows a high canonical correlation (0.884) and a low Wilks’ Lambda (0.0001). Through this analysis, it is possible to observe that the most discriminant activities between both schools were reading pseudowords and writing the names of the pictures presented. As the results of the study by Author (2019) pointed out, students from School 2 present a higher reading development. They achieved a more advanced literacy development in which decoding is automatized and pupils are able to read without using phonological awareness. In addition, these pupils were able to recognize the sounds and write the complete names of the pictures presented.

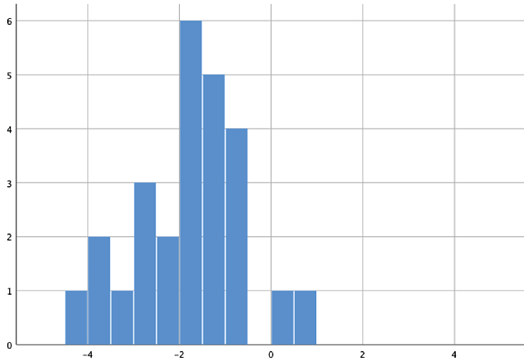

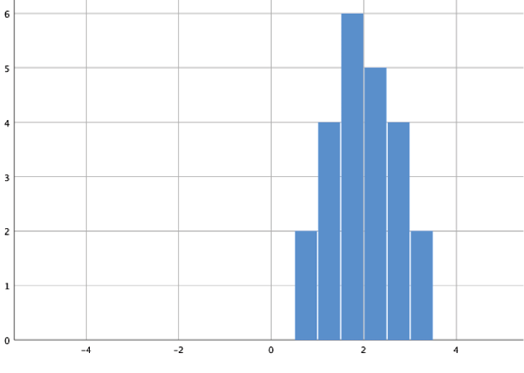

In addition, each school appears on one side of the graph of the discriminant analysis and it is possible to identify students from each centre (See Figure 5 and Figure 6). Students from School 1 seem to present lower and more dispersed scores (Mean=-1.74; SD=1.153) than the students from School 2 (Mean=1.96; SD=0.791).

Figure 5. Score distribution of students from School 1

Source: Authors (2023).

Figure 6. Score distribution of students from School 2

Source: Authors (2023).

Furthermore, the Mann Whitney U Test was calculated in order to compare observations carried out in both schools. Comparing both schools, statistically significant differences were found in favour of School 1 in the use of books (0.001) and the use of worksheets (0.001), which were also used daily; and the type of classroom grouping (0.013). In School 1, activities were carried out daily as a whole group and individually. In the case of School 2, statistically significant differences were found in the use of workbooks (0.002), as this school used them daily instead of worksheets.

Home learning environments

With regard to the first questionnaire focused on reading practices developed in the home environment, the results from Mann-Witney U test presented in Table 3 show that item 1, item 2, item 4, item 7 and item 8 revealed statistically significant differences between both schools (p<0,05). These differences were in favour of School 2 whose mid-ranges (item 1: 26.31; item 2: 27.06; item 4: 25.78; item 7: 28.81; item 8: 26.28) were higher than those found in School 1. In this questionnaire, it was possible to see that parents from School 2 received a higher education (university [n=14] and PhD studies [n=14]) than parents from school 1 who presented a more varied situation (primary [n=2], secondary [n=1], professional training [n=3] and university studies [n=11]). This coincides with the fact that parents from School 2 have more books at home (item 1), which could be related to a higher socioeconomic status.

Table 3. Mid-ranges according to each home environment

|

School |

N |

Mid-ranges |

|

|

1. Do you have books at home? |

1 |

25 |

17.60 |

|

2 |

16 |

26.31** |

|

|

2. Do you usually read newspapers or books in front of your children? |

1 |

25 |

17.12 |

|

2 |

16 |

27.06** |

|

|

3. Do your children read readers* at home? |

1 |

25 |

21.08 |

|

2 |

16 |

20.88 |

|

|

4. Do your children read books at home? |

1 |

25 |

17.94 |

|

2 |

16 |

25.78** |

|

|

5. Do you practice share reading with your children? |

1 |

25 |

19.68 |

|

2 |

16 |

23.06 |

|

|

6. Do your children like to read on their own? |

1 |

25 |

21.48 |

|

2 |

16 |

20.25 |

|

|

7. Do you read books in English? |

1 |

25 |

16.00 |

|

2 |

16 |

28.81** |

|

|

8. Do you read books in English with your children? |

1 |

25 |

17.62 |

|

2 |

16 |

26.28** |

|

|

9. Do your children watch TV in English? |

1 |

25 |

18.62 |

|

2 |

16 |

24.72 |

|

|

10. Do you use the Internet to practice reading with your children? |

1 |

25 |

21.98 |

|

2 |

16 |

19.47 |

|

|

11. Do you use the Internet to practice English with your children? |

1 |

25 |

18.86 |

|

2 |

16 |

24.34 |

|

|

12. Do your children attend English extracurricular lessons? |

1 |

25 |

20.74 |

|

2 |

16 |

21.41 |

|

|

|

|

|

Note: *Books with pictures where children can start reading letters and see pictures and words containing these letters.

**Statistically significant p< 0.01. Source: Authors (2023).

As the second questionnaire investigated the families’ support of the English tasks at home, as can be seen in Table 4, the descriptive analysis revealed the following:

Regarding how many people help children with English tasks, parents normally answered that the mother was the one in charge of performing these tasks. Mothers dedicated more time to help their children in completing English tasks (58 of 103) and they were normally the ones with some English skills (71 out of 103), although at a basic level (certified in some cases).

Table 4. Descriptive analysis. Person in charge of supporting English tasks at home

|

How many people help your child to do English tasks? |

Who spends more time helping your child to do English tasks? | The person who helps your child, does she/he have any English competencies? | |

|

None |

2 |

4 |

0 |

|

Mother |

33 |

58 |

71 |

|

Father |

13 |

16 |

19 |

|

Sister or brother |

4 |

7 |

6 |

|

Grandparents |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

More than 1 person |

45 |

12 |

0 |

|

Other |

6 |

5 |

5 |

|

Total |

103 |

103 |

103 |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Authors (2023).

Regarding the frequency of activities, as shown in Table 5, most of the activities were practiced at home by a high number of pupils either once (reading individual sounds; singing sounds’ songs; reading words; reading sentences) or twice per week (singing English songs; listening to English songs; reading in English). However, a high number of pupils did not practice anything at all at home regarding some activities, such as listening to songs about the letter sounds, watching videos where the letter sounds appeared; using books with stickers; telling tales in English; watching films in English.

Table 5. Descriptive results of the frequency of activities carried out at home

|

School |

Zero times per week |

Once per week |

Twice per week |

Three times per week |

Four times per week |

Five times per week |

|

|

Reading individual sounds |

N |

25 |

29* |

15 |

7 |

3 |

4 |

|

1 |

5 |

9* |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

2 |

20* |

20* |

12 |

5 |

2 |

3 |

|

|

Listening to sounds’ songs |

N |

40* |

21 |

12 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

|

1 |

3 |

7* |

7* |

4 |

1 |

- |

|

|

2 |

37* |

14 |

5 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

Watching sounds’ videos |

N |

44* |

15 |

11 |

6 |

1 |

- |

|

1 |

4 |

7* |

5 |

4 |

- |

- |

|

|

2 |

40 |

8 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

- |

|

|

Singing sounds’ songs |

N |

25 |

27* |

13 |

11 |

7 |

2 |

|

1 |

3 |

9* |

6 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

2 |

22* |

18 |

7 |

10 |

5 |

1 |

|

|

Reading words |

N |

11 |

30* |

26 |

14 |

7 |

4 |

|

1 |

5 |

8* |

4 |

4 |

1 |

- |

|

|

2 |

6 |

22* |

22* |

10 |

6 |

4 |

|

|

Reading sentences |

N |

18 |

26* |

25 |

10 |

5 |

4 |

|

1 |

8* |

6 |

4 |

2 |

- |

- |

|

|

2 |

10 |

20 |

21* |

8 |

5 |

4 |

|

|

Singing English songs |

N |

10 |

24 |

25* |

12 |

6 |

12 |

|

1 |

2 |

6* |

6* |

3 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

2 |

8 |

18 |

19* |

9 |

5 |

10 |

|

|

Books with stickers |

N |

36* |

13 |

11 |

6 |

1 |

2 |

|

1 |

8 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

- |

1 |

|

|

2 |

28 |

10 |

9 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Telling tales in English |

N |

31* |

18 |

10 |

12 |

3 |

3 |

|

1 |

9* |

2 |

2 |

3 |

- |

- |

|

|

2 |

22* |

16 |

8 |

9 |

3 |

3 |

|

|

Listening to English songs |

N |

11 |

16 |

20* |

18 |

7 |

18 |

|

1 |

1 |

7* |

6 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

2 |

10 |

9 |

14* |

12 |

5 |

17 |

|

|

Watching films in English |

N |

27* |

24 |

17 |

8 |

2 |

10 |

|

1 |

11* |

3 |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

|

|

2 |

16 |

21* |

16 |

6 |

2 |

10 |

|

|

Reading in English |

N |

11 |

21 |

24* |

21 |

1 |

6 |

|

1 |

7* |

3 |

2 |

4 |

- |

- |

|

|

2 |

4 |

18 |

22* |

17 |

1 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note: *High frequency. Source: Authors (2023).

Comparison of the activities carried out at home

If each school is taken separately, it can be noticed that, in the case of School 1, the highest frequency of the activities practiced once per week includes the following: reading individual sounds, listening to songs of the phonic sounds, watching videos of these sounds, singing songs of these sounds, reading words, and singing and listening to English songs.

In the case of School 2, the highest frequency of activities practiced once per week is found in reading individual sounds, reading words, reading sentences, singing and listening to English songs, watching films in English, and reading in English.

It is important to highlight that the teacher from School 1 encouraged parents to practice more activities related to the Jolly Phonics method at home. In the case of School 2, teachers did not demand children to work at home with parents as the school promotes children’s autonomy. Therefore, parents from School 2 focused more on practicing English in other ways, such as watching films (Table 6).

Results also revealed statistically significant differences regarding the type of school (Table 6). Comparing both schools, statistically significant differences were found in favour of School 1 in listening to the phonic method’s songs (0.001) and watching videos about the sounds (0.001). In the case of School 2, statistically significant differences were found in reading sentences in English (0.01), watching films in English (0.006), reading in English (0.007), parents’ opinions of children’ ability to read words in English (0.03), and parents’ opinions of children’s ability to read sentences in English (0.001). These results could confirm the fact that parents from each school focused on different activities depending on the teachers’ demands.

Thus, there is a focus on extramural English, which is important for the reading development of children. In fact, in the thesis presented by Rendón Romero (2019), it is possible to observe that pupils from both schools reached the same English reading age. However, there were some differences as pupils from School 2 seemed to be in a lexical route (where children can read and comprehend the meaning of common words) as they were reading at a more advanced level than those from School 1. So, although both schools were using the same phonic method, the same materials and similar activities, these differences between them may rely on the fact that pupils from School 2 received more and different extramural English out of school. The results presented in Table 6 show statistically significant differences in favor of School 2 regarding specific activities, such as watching films in English or using the Internet to practice English at home.

Furthermore, although there were non-statistically significant differences (0.10) regarding the English level and certification of the person who normally helped the child, it was interesting to find that parents from School 2 generally had higher English proficiency levels and in some cases certified.

Table 6. Students’ T-test between schools

| School | Mean |

Standard Dev. |

|

|

How many people help your child to do English tasks? |

1 |

3.36 |

2.158 |

|

2 |

3.18 |

1.905 |

|

|

Who spends more time helping your child to do English tasks? |

1 |

1.68 |

1.626 |

|

2 |

2.09 |

1.637 |

|

|

The person who helps your child, what level of English does he/she have? |

1 |

1.68 |

1.626 |

|

2 |

1.59 |

1.086 |

|

|

English level and certification of the person who normally helps your child. |

1 |

4.08 |

7.756 |

|

2 |

6.99 |

6.121 |

|

|

Frequency of reading individual sounds at home. |

1 |

1.43 |

1.363 |

|

2 |

1.32 |

1.352 |

|

|

Frequency of listening to the sounds’ songs at home. |

1 |

1.68** |

1.086 |

|

2 |

.72 |

1.199 |

|

|

Frequency of watching videos about sounds at home. |

1 |

1.45** |

1.050 |

|

2 |

.53 |

.947 |

|

|

Frequency of singing the methods’ songs at home. |

1 |

1.68 |

1.323 |

|

2 |

1.38 |

1.396 |

|

|

Frequency of reading words at home. |

1 |

1.45 |

1.184 |

|

2 |

2.00 |

1.297 |

|

|

Frequency of reading sentences at home. |

1 |

1.00 |

1.026 |

|

2 |

1.85** |

1.352 |

|

|

Frequency of singing English songs at home. |

1 |

2.05 |

1.432 |

|

2 |

2.22 |

1.561 |

|

|

Frequency of using books with stickers at home. |

1 |

1.13 |

1.500 |

|

2 |

.92 |

1.222 |

|

|

Frequency of telling stories in English at home. |

1 |

.94 |

1.237 |

|

2 |

1.41 |

1.476 |

|

|

Frequency of listening to English songs at home. |

1 |

2.17 |

1.230 |

|

2 |

2.66 |

1.763 |

|

|

Frequency of watching films in English at home. |

1 |

.65 |

1.057 |

|

2 |

1.82** |

1.633 |

|

|

Frequency of reading in English at home. |

1 |

1.19 |

1.276 |

|

2 |

2.16** |

1.265 |

|

|

|

|

|

Note: **Statistically significant p< 0.01. Source: Authors (2023).

2. Discussion and conclusions

The results reveal the fact that key differences exist between the two schools regarding instructional and home learning environments.

Considering the instructional learning environment, different aspects have been analysed. Classroom areas appeared to be different in each school. As opposed to School 2, School 1 did not have enough space to move around the desks or areas for reading activities on the floor. This aspect seems to be important in order to be able to develop group activities properly and to support literacy development (Browne, 2001; Datta, 2007; Jolliffe & Waugh, 2015). Then, it is possible to agree with Neuman & Roskos (2002) on the fact that classrooms need to be “large” and “clear” in order to enable working adequately. In addition, it could be seen that classroom grouping presented statistically significant differences in favour of School 1 where group and individual activities were constantly mixed. In the case of School 2, teachers always started the lesson with group activities then finished with individual work. Thus, it seems that mixing individual and group activities throughout the same session could be beneficial since School 1 presented better results in this sense.

Furthermore, statistically significant differences were found in terms of the teaching materials used in each school. School 2 used more workbooks whereas School 1 used more pupils’ books and worksheets. Although different materials were used, all of them belonged to the same Jolly Phonics method. The results seem to point out that materials used are appropriate in both cases, something important for the development of literacy skills (Browne, 2001; Fons, 2002; Jolliffe & Waugh, 2015; Wright & Peltier, 2016). However, both schools present a high frequency of oral activities, which may suggest the difficulty found in writing activities. This is also related to the fact that the implementation of the phonics method in this study was the first stage of a reading and writing programme.

Regarding the discriminant analysis, it was possible to observe that the most discriminant activity between both schools was reading pseudowords probably because this activity requires remembering individual sounds in order to produce a complete unreal word. Another discriminant activity was writing names of the pictures probably because it requires remembering vocabulary, the pronunciation and the written form of the words. The difference was noticeable considering School 2 as these pupils had achieved a more advanced literacy development (Rendón Romero, 2019) and they performed these two activities better than pupils from School 1. As our analysis points out, it could also be related to the fact that students received different extramural English which could also have influenced their memory in order to remember and write the names of the pictures. Consequently, some differences were found between schools, as parents’ responses from School 1 revealed students had practiced activities related to the phonic method used. In the case of School 2 parents’ responses say that they practiced English with different activities not related to this method, such as listening to English songs or watching English films.

Although our study seems to suggest that socioeconomic status could influence these results, our analysis highlights that extramural English is very important. Consequently, the study posits a possible association between children’s results and the extramural English received, that is, those children who showed higher results at school were also receiving more extramural English at home. Thus, if collaboration between teachers and parents occurs regarding the introduction of extramural English, children’s level will improve regardless of their socioeconomic status. Thus, we coincide with Neuman & Roskos (2002) and Reinders & Benson (2017) on the fact that there should be a link between the class and the learning outside the class to promote such collaboration. We also coincide with Sundqvist (2016) on the idea that this extramural English could be carried out through activities such as watching TV or the use of mobile phones.

Furthermore, our study has also identified differences between the two schools regarding literacy practices at home and parents’ engagement and support on children’s school tasks.

Considering the responses obtained in the parents’ first questionnaire about literacy practices at home, it seems that having books at home, reading in front of children and children reading on their own at home are aspects which may be directly related to the development of English literacy skills. This is the case of School 2, whose parents seemed to be more involved in the literacy practices developed at home in English. This coincides with results presented by Hannon (1995), Harris, et al. (2007), Wood et al. (2018) and Wiescholek et al. (2018). In addition, it may be possible to agree with Alston-Abel & Berninger (2018) who said that home literacy practices correlate with a good achievement of school literacy which, in some way, relates to the idea that parents and children should work in collaboration; and with Datta (2007) who also talks about the benefits of adult guidance in the early literacy process. Hannon (1995) also mentions that the adult functions as a model for children in order to develop reading routines at home. Then, the social factor and practices may provide better results in the development of children’s literacy (Beecher & Makin, 2002; Theodotou, 2017).

Thus, it may be possible to say that practices at home are different depending on some elements, such as school, teacher’s role, parents’ level of English and their participation in their children’s daily literacy practices. In addition, collaboration between parents and teachers could be a good idea to share their opinions in order to work together and help children’s literacy process (Wright & Peltier, 2016; Beecher & Makin, 2002; Theodotou, 2017). So, it is possible to agree with Strasser & Lissi (2009) and Jolliffe & Waugh (2015) on the idea that developing training programs which explain the teaching method used by teachers and suggest parents what they could practice at home seems also necessary in order to support children’s literacy development in English as a Foreign Language.

In conclusion, the connection between the two learning environments analysed in this paper, instructional and home environments, seems to be crucial for a proper literacy development of English as a foreign language. This study also suggests that extra work at home imply a higher achievement at school with better literacy development. Results clearly point out that it is convenient to take into account the extramural exposure during the whole biliteracy process so that what children do at home can promote their own learning. In addition, this could also be an advantage especially in situations, as the one lived during the COVID-19 pandemic, when children had to work at home and parents could be a help for their learning. Thus, it would be necessary to help teachers recommend to parents a variety of extramural activities which could be done at home. Future research could deeply analyse different extramural activities in English in order to be able to suggest the best ones to be used during the early literacy development at home.

[A1]Nota: Este término se suele indicar en mayúsculas ya que es el nombre de una prueba realizada en SPSS, la prueba T de Student. El nombre de Student se le otorgó a esta prueba por William Sealy Gosset, que desarrolló dicha prueba y la publicó bajo el pseudónimo de “Student”.

References

Alston-Abel, N. L. & Berninger, V. W. (2018). Relationships Between Home Literacy Practices and School Achievement: Implications for Consultation and Home–School Collaboration. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 28 (2), 164-189. doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2017.1323222

Bauer, E. B. & Colomer, S. E. (2017). Biliteracy. Recovered on April, 2nd 2019 from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321709458_Biliteracy

Beecher, B., & Makin, L. (2002). Languages and literacies in early Childhood: At home and in early childhood settings. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 10 (1), 67-84. doi.org/10.1080/13502930285208851

Browne, A. (ed.) (2001). Developing Language and Literacy 3-8. (2nd edition). Paul Chapman Publishing.

Caesar, L. G., & Nelson, N. W. (2014). Parental involvement in language and literacy acquisition: A bilingual journaling approach. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 30 (3), 317-336. doi.org/10.1177/0265659013513028

Carroll, J. M., Holliman, A. J., Weir, F. & Baroody, A. E. (2019). Literacy interest, home literacy environment and emergent literacy skills in preschoolers. Journal of Research in Reading, 42 (1), pp. 150-161.

Cuetos, F. (2008). El sistema de lectura: comprensión. In Cuetos, F. Psicología de la lectura (pp. 61-80). Madrid, Spain: Wolters Kluwer Educación.

Datta, M. (2007). Bilinguality and Literacy. Principles and Practice. Continuum.

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K. (2012). Research methods in Education (6th edition). Routledge.

Fons, M. (2002). Aprender a leer y a escribir. In Bigas, M. y Correig M. Didáctica de la Lengua en la Educación Infantil. (pp. 157-178). Síntesis Educación.

Freinet, C. (1974). El método natural de lectura. Laia.

González Álvarez, C. (2003). Enseñanza y Aprendizaje de la Lengua en la Escuela Infantil. Grupo Editorial Universitario.

Hannon, P. (1995). Literacy, Home and School: Research and Practice in Teaching Literacy with Parents. RoutlegeFalmer.

Harris, K. K., Loyo, J. J., Holahan, C. K., Suzuki, R. & Gottlieb, N. H. (2007). Cross-sectional predictors of reading to young children among participants in the Texas WIC program. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 21 (3), 254-268. doi.org/10.1080/02568540709594593

Jolliffe, W. & Waugh, D. (2015). Teaching Systematic Synthetic Phonics in Primary Schools. Learning Matters.

Kern, D., Bean, R., Dagen, A., DeVries, B., Dodge, A., Goatley, V., Ippolito, J., Perkins, H. & Walker-Dalhouse, D. (2018). Preparing reading/literacy specialists to meet changes and challenges: International Literacy Association’s Standards 2017. Literacy Research and Instruction, 57 (3), 209-231. doi.org/10.1080/19388071.2018.1453899

Kokko, A.K., Hirsto, L. (2020). From physical spaces to learning environments: processes in which physical spaces are transformed into learning environments. Learning Environments Research. doi.org/10.1007/s10984-020-09315-0

Lancaster, N. K. (2018). Extramural Exposure and Language Attainment: The Examination of Input-Related Variables in CLIL Programmes. Porta Linguarum, 29, 91-114.

Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. (2012). European Study of Linguistic Competences ESLC. Spanish report. Vol. I. Madrid, Spain: Secretaria General Técnica. http://www.mecd.gob.es

Montessori, M. (2006). Ideas generales sobre el método. Manual práctico. (2nd edition). CEPE.

Neuman, S. B. & Roskos, K. (2002). Environment and its influences for Early Literacy Teaching and Learning. In Neuman, S. B. & Dickinson, D. K. Handbook of Early Literacy Research. (Vol. I), (pp. 281-292). Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

Puglisi, M. L., Hulme, C., Hamilton, L. G. & Snowling, M. J. (2017). The Home Literacy Environment Is a Correlate, but Perhaps Not a Cause, of Variations in Children’s Language and Literacy Development. Scientific Studies of Reading, 21 (6), 498-514. doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2017.1346660

Reinders, H. & Benson, P. (2017). Research agenda: Language learning beyond the classroom. Language Teaching, 50 (4), 1-18. doi.org/10.1017/S0261444817000192

Rendón Romero, S. I. (2019). Bilingual Literacy in Early Childhood Education and Primary Education: The Jolly Phonics Method. (Tesis Doctoral Inédita). Universidad de Sevilla.

Strasser, K. & Lissi, M. R. (2009). Home and Instruction Effects on Emergent Literacy in a Sample of Chilean Kindergarten Children. Scientific Studies of Reading, 13 (2), 175-204. doi.org/10.1080/10888430902769525

Sundqvist, P. (2009). Extramural English Matters. Out-of-School English and Its Impact on Swedish Ninth Graders’ Oral Proficiency and Vocabulary (Dissertation). Karlstad University Studies.

Sundqvist, P. & Sylven, L. K. (2016). Extramural English in Teaching and Learning: From Theory and Research to Practice. Palgrave Macmillan

Theodotou, E. (2017). Literacy as a social practice in the early years and the effects of the arts: a case study. International Journal of Early Years Education, 25 (2), 143-155. doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2017.1291332

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Interaction between Learning and Development. In Cole, M., John-Steiner, V., Scribner, S. & Souberman S. (Eds.). Mind and Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes (pp. 79-91). Cambridge, MA, United Kingdom: Harvard University Press.

Wiescholek, S., Hilkenmeier, J., Greiner, C. & Buhl, H. M. (2018). Six-year-olds’ perception of home literacy environment and its influence on children’s literacy enjoyment, frequency, and early literacy skills. Reading Psychology, 39 (1), 41-68. doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2017.1361495

Wood, C., Fitton, L. & Rodríguez, E. (2018). Home Literacy of Dual-Language Learners in Kindergarten from Low-SES Backgrounds. AERA Open, 4 (2), 1-15. doi.org/10.1177/2332858418769613

Wright, T. S., & Peltier, M. R. (2016). Supports for Vocabulary Instruction in Early Language and Literacy Methods Textbooks. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 32 (6), 527-549. doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2015.1031925

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no financial support nor competing interests to declare.

Authors’ contribution statement

The authors confirm that all of them have participated in the research presented in this paper. Sara Isabel Rendón-Romero: Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing. Macarena Navarro-Pablo: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing. Eduardo García-Jiménez: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Supervision and Writing original draft.

Appendix A. Observation template

Source: Rendón Romero (2019).

Appendix B. First questionnaire about biliteracy practices at home

Source: Rendón Romero (2019).

Appendix C. Second questionnaire about biliteracy practices at home

Source: Rendón Romero (2019).

Rendón-Romero, S., Navarro-Pablo, M., & García-Jiménez, E. (2023). The relationship of home and instructional environments to L2 literacy development. Revista Andina de Educación 6(1), 0006112. Publicado bajo licencia CC BY-NC 4.0